|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

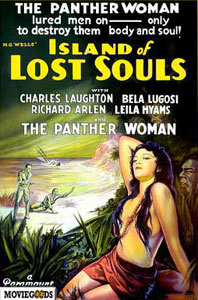

USA 1932 | 70 Minuten

Regie: Erle C. Kenton

Produktion: Paramount Pictures

Drehbuch: Philip Wylie, Waldemar Young (based on the novel The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells)

Kamera: Karl Struss, A.S.C. (s/w, 1.37:1 Academy Ratio 35mm)

Musik: Arthur Johnston (uncredited)

Ton: M.M. Poggi

Bauten: Hans Dreier

Makeup: Wally Westmore

Special Effects: Gordon Jennings

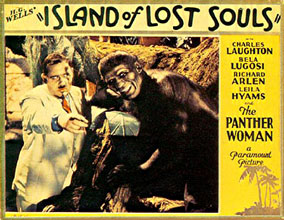

Darsteller: Charles Laughton (Dr. Moreau), Bela Lugosi (Sayer of the Law), Richard Arlen (Edward Parker), Leila Hyams (Ruth Thomas), Kathleen Burke (Lota, the Panther Woman), Arthur Hohl (Montgomery), John George (Beast), Rosemary Grimes (Samoan Girl), Alan Ladd (Ape Man), Randolph Scott (Bit Part, uncredited)

|

|

|

International Movie Database International Movie Database |

All-Movie Guide All-Movie Guide |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

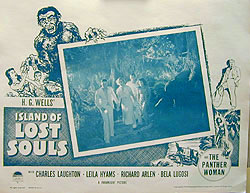

The Island of Lost Souls is that rarity, a horror film from the 1930s that still seems scary. While it may seem a bit creaky by contemporary standards, the film has retained its raw power to unnerve,  thanks largely to Charles Laughton, who brings a vivid, sweaty amorality to his performance that's truly disturbing; lots of mad scientists in the movies have played God, but few made it seem more morally repugnant than Laughton. Make-up man Wally Westmore's creations genuinely resemble a grotesque middle ground between humans and animals; if make-up technique has improved considerably since this film was made, the crudity of the effects actually works in this context, giving Moreau's creations a rough, unpolished quality that suits the story perfectly. And while the film is extremely modest in its onscreen violence, the offscreen mutilations are quite shocking in context; the hideously pained overheard screams of Moreau's "manimals" (and later Moreau himself) are as chillingly effective as a hundred Tom Savini-designed limb-loppings. In its day, The Island of Lost Souls was considered a film that went too far (it was banned in England until the late 1960s), and its rough audacity gives it a power that hasn't dulled all these years later; it's inarguably superior to its latter-day remakes, both titled The Island of Dr. Moreau, after the H.G. Wells novel on which the films were based. thanks largely to Charles Laughton, who brings a vivid, sweaty amorality to his performance that's truly disturbing; lots of mad scientists in the movies have played God, but few made it seem more morally repugnant than Laughton. Make-up man Wally Westmore's creations genuinely resemble a grotesque middle ground between humans and animals; if make-up technique has improved considerably since this film was made, the crudity of the effects actually works in this context, giving Moreau's creations a rough, unpolished quality that suits the story perfectly. And while the film is extremely modest in its onscreen violence, the offscreen mutilations are quite shocking in context; the hideously pained overheard screams of Moreau's "manimals" (and later Moreau himself) are as chillingly effective as a hundred Tom Savini-designed limb-loppings. In its day, The Island of Lost Souls was considered a film that went too far (it was banned in England until the late 1960s), and its rough audacity gives it a power that hasn't dulled all these years later; it's inarguably superior to its latter-day remakes, both titled The Island of Dr. Moreau, after the H.G. Wells novel on which the films were based.

This early adaptation of H.G. Wells' Island of Dr. Moreau is both wonderful and weird. Charles Laughton is in fine form as the calculating mad scientist Moreau, devoted to a bizarre experiment in speeded-up evolution. On his island, he has managed to transform animals into men, and then slaves. Shipwrecked Richard Arlen innocently comes upon this cowering new world, where the locals live in fear of Moreau's "House of Pain" (his laboratory). Moreau attempts to mate the newcomer with his only female creation, Lota, "the panther woman," who seems not uninterested in the match herself. "The film was exceptionally well made. An atmosphere of horror and degeneracy pervaded its every frame. It was not for all tastes: many Midwestern states banned it from release, as did Great Britain and New Zealand" (Parish and Pitts, The Great Science Fiction Pictures). Like other horror films of its time—Tod Browning's Freaks, James Whale's Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein—what makes Island of Lost Souls attractive was precisely what made it repellent: its underlying compassion for the oppressed freak, the beast of scientific progress. The chanting ritual of the island mutants (led by Bela Lugosi) is haunting and strangely beautiful. Arlen innocently comes upon this cowering new world, where the locals live in fear of Moreau's "House of Pain" (his laboratory). Moreau attempts to mate the newcomer with his only female creation, Lota, "the panther woman," who seems not uninterested in the match herself. "The film was exceptionally well made. An atmosphere of horror and degeneracy pervaded its every frame. It was not for all tastes: many Midwestern states banned it from release, as did Great Britain and New Zealand" (Parish and Pitts, The Great Science Fiction Pictures). Like other horror films of its time—Tod Browning's Freaks, James Whale's Frankenstein and The Bride of Frankenstein—what makes Island of Lost Souls attractive was precisely what made it repellent: its underlying compassion for the oppressed freak, the beast of scientific progress. The chanting ritual of the island mutants (led by Bela Lugosi) is haunting and strangely beautiful.

Island of Lost Souls is a masterpiece of '30s horror. Filled with dank jungle settings, dark caves, and huge mutant plants, Island of Lost Souls percolates with a decadent atmosphere that charms while it also horrifies. With director Erle C. Kenton at the helm—who was mostly just a journeyman director with several '40s Universal monster bashes to his credit—the island becomes a sinister, vile environment of creeping shadows that infiltrate right into the souls of the characters on screen. Island of Lost Souls is a masterpiece of '30s horror. Filled with dank jungle settings, dark caves, and huge mutant plants, Island of Lost Souls percolates with a decadent atmosphere that charms while it also horrifies. With director Erle C. Kenton at the helm—who was mostly just a journeyman director with several '40s Universal monster bashes to his credit—the island becomes a sinister, vile environment of creeping shadows that infiltrate right into the souls of the characters on screen.

Richard Arlen plays the shipwrecked Edward Douglas, abandoned much to Dr. Moreau's initial dismay on his South Seas island. Moreau (Charles Laughton) doesn't want any prying ones on his jungle paradise where he conducts medical experiments on animals, but he quickly sees that Douglas could serve a useful purpose.

Moreau leads Douglas around his island, cracking a whip to scare off hulking vaguely-human brutes who leer from the shadows, and introduces him to his daughter, the exotic and strange Kathleen Burke. Moreau immediately arranges for them to share lots of time together. Meanwhile, horrific screams split the night air and the creatures cower while bleating "The House of Pain!"

[...] Laughton's Moreau takes a sadistic glee in his enterprise, eagerly pushing the shipwrecked Edward Douglas together with the almost-human panther woman in hopes that Douglas and she might just sire a child. He waits in the shadows, carefully underplaying his part for the most part, while watching his plot take form. His eyes take on a sparkling glee. Laughton's performance is one of the great performances in the history of screen horror.

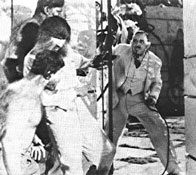

In addition to Laughton's performance, Island of Lost Souls boasts the marvelous cinematography of Karl Struss, one of the great cinematographers of Hollywood, a wonderfully campy performance by Bela Lugosi as the "sayer of the law," who chants "What is the Law?" to the other beasts and a goofy, but creepy bunch of barrel-chested beast men. One of the beasts in particular, practically starts to salivate when he sees Douglas's fiancee arrive on the island. In one delightfully decadent scene, he climbs a tree so he can crawl through a window and into her bedroom.

One of the great failures of the recent remake comes in the scene where the creatures finally turn on Moreau. I won't give away what happens, but in the Brando version, the scene is over all too quickly. While in the original, director Kenton and cinematographer Struss create a horrific vision that is bound to stay with you for years to come. It's one of the great scenes in the history of horror cinema.

There's not a wasted frame in this chilling horror film that was banned in England when released. [...] H.G. Wells, from whose novel the screenplay was written, hated the picture from start to finish because he felt the makers missed his point about a man playing God and opted for the easy way out. The film is steeped in atmosphere and foreboding, and much of the terror was hinted at rather than shown graphically. So many countries (as well as many midwestern states) banned the movie that it took a while to recoup the cost, but Island Of Lost Souls remains, to this day, an eminently scarifying movie. England when released. [...] H.G. Wells, from whose novel the screenplay was written, hated the picture from start to finish because he felt the makers missed his point about a man playing God and opted for the easy way out. The film is steeped in atmosphere and foreboding, and much of the terror was hinted at rather than shown graphically. So many countries (as well as many midwestern states) banned the movie that it took a while to recoup the cost, but Island Of Lost Souls remains, to this day, an eminently scarifying movie.

Of all the 30's horror classics, Island of the Lost Souls is the one most untouched by nostalgia. Its early 30s style (florid acting and dialogue, no background score etc.) never works against it, and far from being cosy, it is as explicit as possibly imaginable. As the two rather embarrassing official remakes (shot, under the title of the H.G. Wells novel, Island of Dr. Moreau, 1977, with Burt Lancaster and 1996, with Marlon Brando) prove, the plot wouldn't be helped by improved technical values or more explicit depictions of violence and/or gore. Actually, as Bryan Senn suggests, Island Of Lost Souls just worked too well: it actually scared people. Small wonder it it wasn't shown in England for 35 years.

Despite H.G. Wells' often-cited disgust with the film, the screenplay is a remarkably intelligent adaption of his novel (dealing with Dr. Moreau's attempts to transform animals into human beings), the one major change being the addition of the "Lota" character — the "Panther Woman of America" contest staged by Paramount as a publicity ploy got newcomer Kathleen Burke the role, and she does quite well with it.

The script-writers were well-fitted for their jobs: Waldemar Young was an old professional working on Lon Chaney scripts (The Unholy Three, West of Zanzibar, London After Midnight etc.), later working on Cecil B. de Mille's Sign of the Cross (1932, with another perverse Laughton performance) and Cleopatra (1934), while Philip Wylie (also a novelist, amongst his books is "When Worlds Collide") authored further jungle melodrams with  Murders in the Zoo (1933, another Paramount horror) and King of the Jungle (1936, a campy adventure). When he resurfaced in 1966, it was for Johnny Tiger, a Robert Taylor vehicle set in the Florida Everglades. Murders in the Zoo (1933, another Paramount horror) and King of the Jungle (1936, a campy adventure). When he resurfaced in 1966, it was for Johnny Tiger, a Robert Taylor vehicle set in the Florida Everglades.

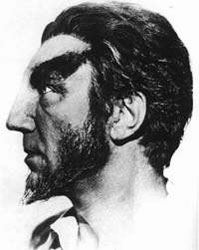

The cast is first-rate. Charles Laughton, fresh from The Old Dark House (1933) based his character portrayal on an oculist and was "not able to enjoy a visit to the zoo since". Leila Hyams starred in Freaks as well, thus being heroine in two of the decade's weirdest movies (she turned down the role of Jane in the 1932 Tarzan). Bela Lugosi (pictured here in an early make-up test, much less hairy than the one ultimately used) is wonderful as "Sayer of the Law".

Under the bizarre and effective makeup some familiar faces are hidden: Alan Ladd, Randolph Scott and Larry "Buster" Crabbe are somewhere amongst the extras, as is stuntman (and strongman) Joe Bonomo in two roles. Hans Steinke, the memorable hunky manimal who broke into Leila Hyams' bedroom, was nominated the World Heavyweight Title by the New York State Athletic Commission in 1928 (see picture). Paul Hurst (Captain Donahue) started out by acting in, writing and directing westerns in 1911. Many of his roles were comedic,  but he also appeared in Gone With The Wind (as the would-be rapist who Vivien Leigh shoots in the face); he committed suicide in 1953. but he also appeared in Gone With The Wind (as the would-be rapist who Vivien Leigh shoots in the face); he committed suicide in 1953.

Everybody is surprised how Erle C. Kenton, a capable workman without much personal style (actually, he was able to add some interesting nuances to his later House of Dracula (1945), including a direct quote from Island of Lost Souls), was able to pull off a unique wonder like Island of Lost Souls. Actually, there is no surprise involved, just some very competent artists working together on a film based upon a strong and original plot just before the advent of the Hayes code. Make-up artist Wally Westmore had had some opportunity to dabble in the macabre when working on Fredric March in Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1932). Photographer Karl Struss peppers the film with odd, unexpected touches, like the hasty panning shot over a couple of bare-chested seamen which more or at the beginning of the film, or the sustained shot of the pool during a scene between Burke and Arlen.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

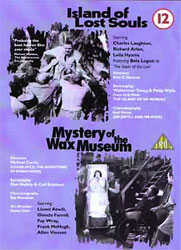

DVD

|

Islands of Lost Souls / Mystery of the Wax Museum

Visionary Communications Ltd

|

| Länge: |

67:13 min (= 70 min PAL)

|

| Video: |

|

| Bitrate: |

|

| Audio: |

- English Dolby Digital 2.0 Mono

|

| Untertitel: |

|

| Features: |

|

| DVD-VÖ: |

26 Februar 2001 |

|

Chapters: 5

Keep Case

DVD Encoding: Region 0 (UK)

SS-SL/DVD-5 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg) |

|

|

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)