|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Cat People

(Katzenmenschen | La féline)

|

|

|

| |

|

USA 1942 | 73 min

Regie: Jacques Tourneur

Producer: Val Lewton

Production Company: RKO Radio Pictures

Screenplay: DeWitt Bodeen

Cinematographer: Nicholas Musuraca, A.S.C. (b/w, 1.37:1 Academy Ratio 35mm)

Editor: Mark Robson

Music Score: Roy Webb

Sound: John L. Cass (Mono)

Art Director: Albert S. D'Agostino, Walter E. Keller

Set Director: Al Fields, Darrell Silvera

Budget: $134,000

Shooting: RKO Studios Hollywood, 28 July–21 August 1942

Cast: Simone Simon (Irene Dubrovna), Kent Smith (Oliver Reed), Tom Conway (Psychiater), Jane Randolph (Alice Moore), Jack Holt (Commodore), Alan Napier (Carver), Elizabeth Russell (The Cat Woman)

Premiere: 16 November 1942 (USA) | 3 July 1974 (West Germany, TV West3)

|

|

|

International Movie Database International Movie Database |

All-Movie Guide All-Movie Guide |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

First in the wondrous series of B movies in which Val Lewton elaborated his principle of horrors imagined rather than seen, with a superbly judged performance from Simon as the young wife ambivalently haunted by sexual frigidity and by a fear that she is metamorphosing into a panther, with its chilling set pieces directed to perfection by Tourneur, it knocks Paul Schrader’s remake for six, not least because of the care subtly taken to imbue its cat people (Simon, Russell) with feline mannerisms. Its sober psychological basis is barely shaken by the studio’s insistence on introducing, as a stock horror movie ploy, a shot of a black panther during one crucial scene.

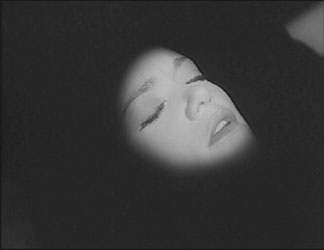

The Lewton-Tourneur low-budget technique relied on implication rather than explication; in a universe of shadows and off-screen sounds lurked the veritable soul of terror. The delicate poetry of the original Cat People, both as a horror film and as a psychological study of female sexuality, is really quite unique in cinema. Simone Simon portrays Irena, a Serbian immigrant in New York who fears that she has inherited a curse that will cause her to turn into a cat should she become sexually aroused. This preposterous supposition is made entirely palatable in small doses of believability (it comes in on little cat’s feet) and by Irena’s utter earnestness, and utter vulnerability, in attempting to overcome her problem. Moreover, the threat that stalks Irena through the urban nightscape is both within her and without her: the help of a sinister psychiatrist is dubious at best, and her new husband begins to stray. The two-fold betrayal brings on one of the most suggestive, frightening, and justifiably feline jealous rages ever filmed.

A lyrical interpretation of female sexuality, Cat People is also several steps more evolved than King Kong in terms of bringing the primitive home to Manhattan, for it deals with human transformation or, literally, transfiguration. Believing she is possessed by a panther’s spirit, Irena spends hours at the zoo, drawing morbid pictures of large cats transfixed by swords. Thus plagued by lycanthropy, the young fashion illustrator rapidly assumes predatory traits of the feline demons when she falls in love with Oliver. Suffice it to say that the arousal of insane sexual jealousy serves as the catalyst which unleashes a ferocious feline terror. Tourneur’s allusive orchestration of camera movement, shadow, and sound crystallizes in some of the most chillingly satisfying sequences of horrific cinema.

Lewton’s first production, Cat People (1942), set the tone for the remainder of his output and used many of the personnel — director Jacques Tourneur, writer DeWitt Bodeen, cameraman Nicholas Musuraca, set designer Albert d’Agostino, editor Mark Robson, performers Kent Smith, Simone Simon, Tom Conway — who collaborated with him later. It was the story of Irene Dubrovnik (Simon), a Balkan-born girl working as a dress designer in New York who under stress becomes an outsize homicidal cat. Careful — perhaps over-careful the film today seems so understated that much of its intended effect is dissipated. But it remains full of atmosphere and benefits enormously from Musuraca’s exquisite low-key photography and d’Agostino’s cosy, intimate art direction. Its high-spots — Jane Randolph pursued by some nameless, snarling Thing through a nocturnal Central Park, and threatened by a similarly insubstantial horror in an otherwise deserted basement swimming-pool — still carry a potent charge, but its total impression is distinctly tepid.

Charles Higham, Joel Greenberg: Hollywood in the Forties

London-New York 1968, p. 59

Cat People, with its totally manufactured variation on the Werewolf theme, eschews all of the standard effects of fog, creaking doors, trick photography, and monstrous changeovers. Working on Lang’s old premise that nothing that the camera can show can possibly be as horrible as what the mind can imagine, it shows nothing and suggests all. (Only once is an actual leopard shown in a supernatural context; Lewton fought against it, but was overruled. However, it does little damage, as the scene can still be interpreted as a subjective imagining on the part of the trapped hero and heroine.) The backgrounds are modern, normal, and unspectacular, unglossy studio reconstructions of New York’s offices, museums, Central Park Zoo, and environs. The people are ordinary, even dull and pompous. While the moments of horror are ambiguous and fragmented, the film leaves one with the deliberately uneasy feeling that the only explanation must be an acceptance of the supernatural. The episode in which the heroine, swimming in a darkened hotel swimming pool, is menaced by the unseen presence of the Cat Woman—or by a real leopard—is not only a classic episode of economical screen terror, it works on a second level too, since its symbolic imagery is essentially Freudian. With its basically realistic setting, and its logical use of light, shadow, and distorted sound, it is a perfect example of the Fritz Lang modus operandi, of turning the everyday into a black, nightmare world of unseen menace.

William K. Everson: Classics of the Horror Film. Secaucus, N.J. 1974, S. 183

... By 1942 Lewton found himself with a curious hankering for the finer things, even on poverty row. Universal had a virtual monopoly on vampires, monsters, mummies, and werewolves and such. RKO was thus compelled to turn to wild animals and zombies, both more or less in the public domain. Lewton's first project became the instant classic, Cat People, through a variety of low-budget coups with the writing, the direction, and the casting. Lewton recruited De Witt Bodeen as script writer and Jacques Tourneur as director, but Simone Simon virtually fell into his lap after this French star, like her unhappy compatriot, Danielle Darrieux, had failed to establish a viable Hollywood career. The feline beauty of Simone Simon lifted Cat People far above the usual level of B pictures. The original story had been set abroad, but it was Lewton's inspired decision to shift the locale to America that made Simon even more effectively exotic. Seen today, Cat People mixes the ordinary with the occult to create a subtler and more believable terror than would be possible in such hackneyed locales of the horror genre as Transylvania or foggy London town. RKO executives were terrified by the first rushes of Cat People with their measured pacing and matter-of-fact mildness. Yet, after some initial restiveness, sneak preview audiences came alive with the sudden bursts of terror, all the more exciting for arising out of a slowly suspenseful buildup.

... By making a virtue of necessity, Lewton had shown in Cat People an ability to produce gripping subtexts from what started out as penny-dreadful material and publicity. He established a standard of empathy and sympathy with the twisted fantasies of the horror genre that has proven to be inimitable in subsequent decades.

... Kent Smith played the equivalent of the Oliver role, though as an architect rather than a zoologist, and Jane Randolph played the equivalent of the Alice role. Though Smith was an accomplished Shakespearean actor on the stage, the screen invested him with the aura of a B-picture leading man. The character he plays in Cat People is dull, conformist, humorless, and unimaginative. Revival audiences in the Fifties giggled at his unexpectedly overwrought love scene with Randolph. Still, Smith and Randolph had served audiences in the Forties as adequate raisonneurs to carry the plot past its more lurid speculations. At the center of the film was the sweetly menacing eroticism of Simone Simon as the mysterious cat person from Yugoslavia. It was wartime, remember, and one did not have to write much exposition for a presumed refugee.

It was also a time of heavy censorship and sanctimoniousness, a time on the screen when all sorts of forbidden impulses were beginning to surface, only to be submerged by a kind of common man, common sense puritanism. Consequently, Simone Simon's Irena must die, not so much for any consciously malevolent act, but rather for arousing the dread demons of desire in a dull society. Irena is not the only victim of the anti-sex furies of Cat People; a womanizing psychiatrist, played by Tom Conway, must be disposed of as well since he seeks to profit carnally from his insight into Irena's bestial-sexual nature. The Conway character is not a bad sort otherwise. In, deed, he and Irena project a civilized European sensibility completely lacking in the other characters. But in 1942, American audiences were unduly smug about the "normality" of their own society, and Irena and the psychiatrist were therefore unsettling representations of Old World decadence.

Andrew Sarris: Val Lewton: RKO's Prince of Darkness.

TPV Archives (Volume 5, Issue 20, Winter 1994)

Avant tout, ne pas oublier qu’il s’agit là d’un film essentiel, non seulement dans la carrière de ses deux principaux artisans (le producteur Val Lewton et le réalisateur Jacques Tourneur), dans l’histoire du genre fantastique, mais aussi et surtout dans l’évolution du cinéma tout entier. Borges a consacré une de ses enquêtes, « La pudeur de l’histoire », à montrer que les dates les plus importantes de l’histoire ne sont pas forcément les plus spectaculaires. « Le soupçon m’est venu, écrit-il, que l’histoire, la véritable histoire, est plus pudique, et que ses dates essentielles peuvent aussi demeurer longtemps secrètes ». Cela, qui est vrai de l’histoire politique et sociale, l’est plus encore de l’histoire esthétique. Cat People représente dans le cinéma une de ces dates essentielles et secrètes. La genèse du film est assez bien connue puisque Jacques Tourneur et le scénariste DeWitt Bodeen l’ont racontée (respectivement in « Présence du cinéma » no 22-23, 1963 et « Films in Review », avril 1963) et que Joel E. Siegel, dans son remarquable « Val Lewton. The Reality of Terror », Seeker and Warburg, Londres, 1972, a recueilli les témoignages des proches du producteur. Charles Koerner, le nouveau responsable de la RKO, demande à Val Lewton de préparer un film à partir du titre Cat People qui lui paraît excitant et attractif à souhait. Il estime que les monstres de l’avant-guerre (vampires, loups-garous, etc.) ont fait leur temps et qu’il faut chercher quelque chose de nouveau et d’insolite. Val Lewton commande le scénario à DeWitt Bodeen et la mise en scène à Tourneur. Mais l’histoire elle-même sera concoctée à trois.

Val Lewton avait d’abord pensé adapter une nouvelle d’Algernon Blackwood puis décide de raconter une histoire contemporaine, inspirée d’une série de dessins de mode français qui montraient des modèles portés par des mannequins à têtes de chats. Chacun des trois auteurs apportera sa pierre à l’édifice et, par exemple, la scène de la piscine sera suscitée par un souvenir de Tourneur qui avait manqué se noyer, seul dans un bassin. Lewton affectionne particulièrement ces moments d’angoisse, comme la scène où Alice se sent poursuivie par une présence invisible. Tout va passer, au stade de l’écriture comme au stade de la réalisation, par la suggestion, par une progression savante de scènes exprimant la terreur et la violence sans qu’elles soient jamais représentées tout à fait sur l’écran. Les paroxysmes seront obtenus par une certaine douceur insidieuse et paradoxale du style, qui s’attache à suivre de très près les personnages et les plonge dans une atmosphère de plus en plus irrespirable que le spectateur est amené à partager avec eux, quoiqu’elle ne provienne d’aucun élément horrifique concret. Tourné en 21 jours et pour un budget assez modeste de 130 000 dollars, Cat People sera le premier d’une série de quatorze films produits par Val Lewton (dont 11 pour la RKO) et, dans la carrière de Tourneur, le premier où il est devenu véritablement lui-même grâce à l’influence ultra-créatrice de son producteur. Celui-ci l’initia, dit-il, à « une poésie dont il avait bien besoin » (cf. son interview télévisee pour FR3 par Jean Ricaud et Jacques Manley, mai 1977). Une fois terminé, le film est fort peu apprécié des patrons de la RKO et sortira en bouche-trou au Hawaï Cinema de Los Angeles qui venait de terminer l’exploitation de Citizen Kane. Cat People fit mieux que son illustre devancier, et son triomphe remit sur pied la RKO en 1941, année très difficile pour la firme. Cat People permit à Val Lewton de produire entre 1942 et 1946, toujours avec des budgets très réduits qui lui assuraient une totale liberté de conception et d’exécution, l’un des plus extraordinaires ensembles de films fantastiques du cinéma hollywoodien (d’où se détachent particulièrement le sublime Seventh Victim et Bedlam qui clôt la série).

Cat People lança aussi la vraie carrière de Jacques Tourneur qui donna ensuite dans la même lignée deux oeuvres encore plus parfaites (I Walked With a Zombie et Leopard Man) avant de jeter un regard profondément neuf sur les autres genres hollywoodiens où il s’illustra. Plus les années passent, plus l’apport du film paraît incalculable. Avec lui, le fantastique — qui ne sera jamais plus pareil — découvre qu’il peut tirer son efficacité maximum de la litote, qu’il peut inventer de nouveaux moyens d’empoigner le spectateur en s’adressant à son imagination. La richesse du travail sur la lumière notamment contribuera à intérioriser le contenu du film dans les personnages et à provoquer une identification plus subtile et plus poussée du spectateur avec ces personnages. C’est là que se situe, avec pudeur, la révolution radicale de ce film. On peut la résumer d’un mot : c’est la révolution de l’intimisme. Elle dessine pour ainsi dire une ligne de fracture entre le cinéma d’avant-guerre et le cinéma moderne. Ce que le cinéma va y gagner, c’est une plus grande proximité, une plus grande intimité — qu’on pourrait presque qualifier de psychique — du spectateur avec les personnages, explorés dans le tréfonds de leurs peurs, de leurs angoisses, de leur inconscient. Cet apport n’est pas contradictoire, loin de là, avec celui du néo-réalisme qui aboutira lui aussi, au moins chez Rossellini, à augmenter l’intimité du spectateur sur un plan social et bientôt spirituel avec les personnages. Le recul est maintenant suffisant pour que Cat People et les premiers films de Rossellini après guerre apparaissent, l’un secrètement et souterrainement, les autres d’une manière spectaculaire et peut-être trop tonitruante, comme les films les plus féconds de ces cinquante dernières années. Le cas de Cat People est particulièrement étrange puisquil nous amène à avoir plus d’intimité avec un personnage (celui de Simone Simon) qui ne peut en avoir avec personne. Sa malédiction est enfouie à l’intérieur de lui-même et si profondément que seule une investigation de type plongée dans les grands fonds peut permettre de la faire entrevoir. Avant ce film, le cinéma était ce miroir plus ou moins fidèle promené le long du chemin. A partir de Cat People, il tendra à devenir cet instrument de plongée qui descend au plus profond des personnages comme dans un puits. Pendant les années qui suivront, le courant du film noir renforcera cette évolution en mettant à son service, sous une forme actuelle et contemporaine, les acquis lointains de l’expressionnisme maries a une découverte récente et souvent rudimentaire de la psychanalyse. Point de départ de l’œuvre réelle de Tourneur, Cat People cerne bien ce qui va être le credo de cette oeuvre et son mode d’approche de la réalité. Toute réalité est de l’ordre du mystère, de l’étrange, de l’ineffable. Il faut l’appréhender de l’intérieur, par la suggestion et l’imagination. Le regard qui ira le plus profond en elle a toutes chances d’être celui d’un étranger, et Tourneur restera en Amérique l’un des cinéastes les plus étrangers à ce pays, en proie à une surprise continuelle, à une totale et ingénue disponibilité. Elles feront de lui un pionnier secret, un éclaireur explorant de nombreux territoires quelques instants avant tout le monde.

Jacques Lourcelles: Dictionnaire du cinéma. Vol. III: Les Films

Paris 1992, S. 543-545

An important lesson Lewton learned as a child was that a single folktale could be told and retold, its quality of interpretation dependent upon the person doing the telling. Some storytellers embellished the tale with gore and lingered upon the morbid details; others used darkness, the unseen, the unstated, to mine their chills. Val Lewton, a born raconteur, would take this knowledge to heart.

Now he and his screenwriter, DeWitt Bodeen, were about to prove their worth as storytellers. In Joel E. Siegel’s The Reality of Terror, Bodeen recalls his early days with Lewton. After the latter left for RKO, Bodeen remained with Selznick an additional two weeks, putting some finishing touches on the Jane Eyre Selznick package that would eventually be sold to Fox. Meanwhile, Lewton arranged to have Bodeen hired by RKO at $75 a week. Once reunited, Lewton and Bodeen embarked upon an extensive study of the cat in literature. For a time, the two men dallied with the notion of adapting Algernon Blackwood’s short story, "Ancient Sorceries,” for the big screen. Two other short stories were also considered: Ambrose Bierce’s "The Eyes of a Panther” and Margaret Irwin’s "Monsieur Seeks a Wife.” Ultimately, Lewton vetoed these proposals and decided to do an original story set in contemporary New York. In My Brother, Lucy Lewton tells us that Val’s contemporary story was inspired, in part, "by a series of French fashion designs … drawings of gowns worn by models with the heads of cats.”

Lewton then began thinking of a director, his first choice being his A Tale of Two Cities partner, Jacques Tourneur. Remaining on the MGM lot after Selznick and Lewton left, Tourneur had made a series of dramatic shorts (covering everything from adaptations of famous short stories to realistic "crime does not pay” shorts. In 1939 Tourneur directed his American feature film debut, They All Come Out. Although it was a low-budget production, the first half of this film is a striking precursor to the film noir style that would dominate the 1940s. Tourneur also directed lively "B” budget "Nick Carter” entries like Nick Carter, Master Detective (1939) and Phantom Raiders (1940), showing considerable directing flair with the programmer material he had been given.

Over the years, Lewton and Tourneur remained in touch with one another, indulging in occasional boating weekends with their combined families. When Lewton asked his friend to direct Cat People, Tourneur was available and happy to comply. Lewton arranged to have him signed on at RKO.

In the spring of 1942, while Robert Wise was still struggling over the monumental task of a final edit for The Magnificent Ambersons, his former assistant, Mark Robson, was sent over to the horror production unit as Lewton’s adviser and cutter. Robson had just finished editing the Orson Welles/Norman Foster collaboration, Journey Into Fear.

Lewton’s first business was to put into practice the experience he had gained working under Selznick, though he was not inclined to exploit his employees the way Selznick had exploited him. Mark Robson once characterized Lewton as "a benevolent David Selznick.”

Jacques Tourneur later told Charles Higham and Joel Greenberg (in The Celluloid Muse):

"[Lewton] would originate the ideas for our films, and then call in the writers, myself, and the editor, Mark Robson, and we were encouraged, over cups of tea, to say anything "wild.” ... Val was so conscientious! I’d go to a film or a theatre downtown, and my wife and I would be driving back ... at half past one or two in the morning. And always, as we passed the studio, we’d see a light in that corner office of his, and he’d be alone working, correcting what the writer had written; he could only work at that time of night. Next day he’d hand the work to us.”

Lewton’s own phobia of cats added a degree of resonance to the Cat People project. Years earlier he had written the effective "cat werewolf”’ story, "The Bagheeta,” for Weird Tales magazine. Anecdotes of Lewton’s unnatural fear of felines are numerous. In 1934, while Lewton crossed the country by train, scouting out his new Hollywood job with Selznick, his sleep was troubled by recurring nightmares involving cats (Siegel, Reality of Terror). Ruth Lewton recently told the author that if her husband was keeping a late night writing vigil and a neighborhood cat began to howl, he would hurry into her room so as not to face his fear alone. One can easily understand Lewton’s discomfort during the gestation of Cat People when he was writing and rewriting the script in those wee hours of the morning as he was prone to do.

Lewton’s original story was set to open in a snowbound Balkan village recently occupied by a Nazi Panzer division. By day the village inhabitants are docile and cooperative; by night they become carnivorous beasts who reduce German soldiers to shredded uniforms. After the slaughter, a girl flees the village, travels to New York, and falls in love. At the time, Lewton’s idea was to have the girl’s words remain unintelligible to the audience, her lines spoken in long shots. According to Lewton, "You hear the murmur of her voice, you never hear what she is saying and, if it is necessary to give her words meaning to the audience, I think we can always contrive to have some other character tell what the girl said” (George Turner, "Val Lewton’s Cat People,” Ciné fantastique, vol. 12, no. 4).

Turner also quotes Lewton as having several interesting ideas that never made it into the film:

"Most of the cat werewolf stories I have read and all the werewolf stories I have seen on the screen end with the beast gunshot and turning back into a human being after death. In this story I’d like to reverse the process. For the final scene I’d like to show a violent quarrel between the man and woman in which she is provoked into an assault upon him. To protect himself, he pushes her away, she stumbles, falls awkwardly, and breaks her neck in the fall. The young man, horrified, kneels to see if he can feel her heart beat. Under his hand black hair and hide come up and he draws back to look down in horror at a dead black panther.”

Most of Lewton’s original ideas so defied convention that Lew Ostrow, who disliked some of Lewton’s pretentions, was ready to throw in the towel and perhaps seek a more appropriate producer for horror programmers. Fortunately, Charles Koerner went to bat for Lewton who, though encouraged to revise along more conventional lines, managed to retain some of his original ideas. Koerner was impressed by some of Lewton’s notions, and the two men had an appreciation for one another.

Eventually, Lewton discarded the exotic Balkan setting when he hit upon the idea of bringing the entire film closer to home. He reasoned: "The characters in the run-of-the-mill weird films were usually people very remote from the audiences’ experiences. European nobles of dark antecedents, mad scientists, man-created monsters, and the like cavorted across the screen. It would be much more entertaining if people with whom audiences could identify were shown in contact with the strange, the weird, and the occult” (Turner, "Cat People”).

In an attempt to create this sense of normalcy, Lewton would plan sets that looked lived in. If characters occupied an apartment, props would be typically arranged to reflect the tastes of the apartment’s owner; if a workplace was shown, the environment would reflect work in progress. To create an illusion of normalcy, Lewton would avoid the pristine, tidied-up interior sets so common at the time.

Jacques Tourneur came up with an idea for a terror sequence that was based on an experience he had had some years earlier while swimming alone in a friend’s pool. The friend, whose pool Tourneur frequented, kept two pet cheetahs. Tourneur tells us:

"And one day I’ll be damned if one of the cheetahs wasn’t out o is cage and starting to prowl around and growl in a low way, and I thought, "Oh my God, here I am feeling naked, I can’t scream,” and I was going around in circles in the nude. … Luckily, the cheetah was afraid of the water. And eventually, from way back on the property somewhere, the gardener came with a rake and shooed the cheetah back.” [Higham and Greenberg, The Celluloid Muse].

A matter of pressing importance during Lewton’s first month on the Cat People project was obtaining the appropriate actress for the title character. Lewton told Lew Ostrow: "I took a look at the Paramount Picture The Island of Lost Souls and after seeing their much publicized ’panther woman,’ I feel that any attempt to secure a cat-like quality in our girl’s physical appearance would be absolutely disastrous” (Turner, "Cat People”).

Then, while Lewton was screening RKO’s All That Money Can Buy (1941), a coquettish French actress, Simone Simon, caught his eye: "I’d like to have a girl with a little kitten-face like Simone Simon, cute and soft and cuddly and seemingly not at all dangerous,” he wrote Ostrow (Turner, in "Cat People”).

Simone Simon, born in 1910, had made her screen debut in Le Chanteur Inconnu, a 1931 French film. She came to America in the mid-1930s, starring in Girl’s Dormitory and Seventh Heaven before going back to her native France in 1938. In 1941 Simon returned to Hollywood for William Dieterle’s All That Money Can Buy, which inspired Lewton to acquire her talents. Although Simon had already journeyed back to her native home, Lewton was able to talk his superiors into offering her the lead role.

After Lewton and DeWitt Bodeen worked out their basic storyline for Cat People, Lewton assigned Bodeen to write a complete treatment in short story form. Lewton called for a first-person narrative written by Alice, the character in love with the "cat woman’s” husband. Lewton then instructed Bodeen to model the Irena Dubrovna "cat woman” role upon the actress Simone Simon, which he did. Bodeen, already in tune with Lewton’s aesthetics of terror, included dark, shadowy passages suggesting, rather than displaying, the presence of horror. When the piece was finished, it was sent to Simone Simon, who read the treatment and quickly accepted the role.

While Bodeen prepared the treatment, Lewton received some sage advice from RKO "B” veteran, producer Herman Schlom, who revealed ways of cutting preproduction costs by writing around preexisting sets and dressing them up a bit so that they would not be readily recognized. Lewton found he could make use of a Central Park set from an Astaire/Rogers musical as well as an office workplace from the 1941 Jean Arthur film, The Devil and Miss Jones. A standing cafe set was dressed and redressed to function as a coffee shop, a pet shop, and a restaurant.

After scouting the flexibility of set locations, Lewton had to concentrate on the remainder of his cast. For the wholesome male lead, an ex-Broadway leading man named Kent Smith had captured Lewton’s attention. Although Smith had been under contract to RKO since 1941, he had done little work except for some Army training films. Lewton saw Smith commuting back and forth to the studio every day on his bicycle, and the neophyte producer was taken by his solid good looks and healthy appeal. Lewton moved quickly, obtaining Kent as Cat People’s leading male character, Oliver Reed.

The second female lead, Oliver’s working associate, Alice, was not as easily secured. Lewton sought the talent of a new Selznick discovery, Phyllis Isley. Although Isley had worked in films before, being taken under Selznick’s wing, it was Lewton who suggested she change her name to Jennifer Jones. Selznick, who was convinced of his proteg6e’s genuine star potential, accepted the new moniker but nixed the idea of her taking part in a "B” film.

Mark Robson may have been of some help in securing Jane Randolph for the role of Alice. Robson had just recently finished editing an entry in RKO’S "Falcon” series, The Falcon’s Brother, which starred a pert and likeable Randolph in the female lead. Although Lewton initially had another choice in mind for psychiatrist Dr. Louis Judd, his screening of the "Falcon” picture convinced him that Tom Conway, who had just replaced his brother (George Sanders) as the lead in the series, would be an ideal choice for the role of an articulate and debonair heel.

The rest of the players were mostly contract actors handpicked from the RKO rosters by Lewton and Tourneur. One very significant small role came about when Lewton, at a cocktail party, bumped into a statuesque model and sometime actress named Elizabeth Russell. Lewton did not want an actress who resembled a cat to carry his lead role, but he could not resist using Russell’s austere feline beauty in a key scene. Although lasting only moments, the economy of Russell’s cameo is wondrous and it remains etched in viewers’ memories long after the more essential concerns of plot and character have been all but forgotten.

Lewton surrounded himself with the best technicians the studio had to offer. Nicholas Musuraca, the cinematographer from Stranger on the Third Floor, was advised to continue his expressionistic style for Cat People; his photography became instrumental in establishing the film’s classic set pieces. The estimable talents of house art directors Albert S. D’Agostino and Walter E. Keller were also put to good use.

For Cat People’s musical score, the front office urged Lewton to use the generic canned music RKO had in its vaults, including its oft-used pastiches of Max Steiner scores. However, even before the actual screenplay was prepared,, Lewton consulted composer Roy Webb and musical director Constantin Bakaleinikoff for a proposed original score. Like the musical leitmotifs Franz Waxman prepared to correspond with characters and situations in The Bride of Frankenstein, Lewton wanted to link his visuals with music, but this again raised eyebrows at the front office. Roy Webb was assigned the task of writing the score and would do the same for the vast majority of Lewton’s RKO efforts. For Cat People, Webb scored seven separate themes (including a lovely lullabye), each centering around the main character, Irena Dubrovna.

Webb, a graduate of Columbia University (and composer of the university’s "fight song”) was a cofounder of ASCAP in 1914. He came to Hollywood in 1929, near the beginning of the sound era, and joined RKO in 1935, becoming assistant to Max Steiner. Although he did some supervisory work for other composers in Gunga Din, Citizen Kane, and Kitty Foyle, Webb’s first original score was for Alice Adams (1935). He also composed the score for The Stranger on the Third Floor (1940).

On July 6, 1942, The Hollywood Reporter announced that even before shooting had begun on Cat People, RKO had already assigned Lewton a property called I Walked with a Zombie. Elsewhere, the periodical mentioned that Simone Simon had just arrived in America for her "personal tour in the East which she will cut short to report at the studio for a July 21 start.”

Under Jacques Tourneur’s direction, Nicholas Musuraca’s cameras began to roll on July 28, 1942, for Val Lewton’s production of Cat People. Four days later, things got shaky when Lew Ostrow viewed the rushes and, not liking the results, threatened to replace Tourneur with a studio contract director. Lewton managed to stay Ostrow’s hand until Charles Koerner, who was away on business, returned and could be consulted. The next day, Koerner looked at the rushes and could not understand what Ostrow was complaining about; he declared that Tourneur was doing just fine and should be left to his own business. Ostrow offered little interference after that.

The August 3 Hollywood Reporter announced that Cat People was six days into production and that two units were "shooting round-the-clock,” a night unit shooting with animals and a day unit shooting with the major performers.

Lewton felt a need to impress his superiors with the speed of his production, thinking it would improve his chances of gaining some degree of autonomy, but Koerner and Ostrow could not be so easily mollified by economy of production. Koerner voiced a few complaints concerning Lewton and Tourneur’s tendency to leave too much to the imagination, and the filmmakers had to comply (minimally) with their superiors’ wishes.

George Turner, in his article "Val Lewton’s Cat People,” comments upon the meticulous efforts afforded the sound track and records the front office’s reaction to such tomfoolery:

"When the cost accounting office demanded to know why John Cass’s recording crew worked an extra three days on Cat People, it was explained that they spent one day at Gay’s Lion Farm recording the growls and roars of the big cats and two days at the indoor swimming pool of the Royal Palms hotel recording reverberation effects. A vocal effects actress, Dorothy Lloyd, was hired to create the cat noises. The studio bosses regarded all this as unusually extravagant for a "B” picture.”

Except for the expected amount of friction from the front office, Cat People’s production was smooth sailing. Shooting ended on August 21, ahead of schedule. Although the original proposed budget ($118,948) had been revised to $141,659 shortly after production had begun, Lewton managed to bring the film in at $134,959. Some of the department heads believed Lewton was taking an undue amount of care with postproduction particulars on what they felt was, after all, just another "B” programmer, but Lewton stood his ground.

Finally, Lewton and Tourneur ran the completed film for their studio bosses. After the screening, there was dead silence. Koerner refused to speak to either of them and left in a hurry. Only Ostrow stayed behind to nag the filmmaking duo about Cat People’s profound lack of horrific content.

Lewton was not encouraged by this cold reception, especially since he was by this time already deeply enmeshed in his second production and about ready to begin his third. Several weeks later’ the Lewton unit attended the first public preview at the Hillside Theatre, a Los Angeles movie house known for its rowdy clientele. In Joel E. Siegel’s The Reality of Terror, Bodeen recalled the Hillside Theatre preview, telling us that "Val’s spirits sank lower and lower” when the preceding cartoon, an animated Disney short featuring "a little pussycat,” provoked the audience into catcalls and mewing sounds. Things took a more disturbing turn when Cat People’s title hit the screen, "greeted with whoops of derision and louder meows.” Fortunately, the film thereafter worked its dark magic upon the audience and the latter, having become intrigued by the credible story and sympathetic characters, responded well to the film’s terror highlights, emitting gasps and screams in all the appropriate places.

The press began to unleash their reviews on Friday, November 13,1942, and they were mixed. Some were wildly favorable; others were caustic, calling the movie "fantastic and unhealthy” or "morbid and unproductive.” None of the reviews, even those partial to the film, prepared anyone for the forthcoming "sleeper” status of Cat People. Word of mouth escalated the film’s worth by the time of its general release in December (when it was inexplicably paired with the misleadingly titled nonhorror film Gorilla Man), and it began playing to sellout crowds.

The bewildered critics went back to see it a second time and admitted their initial hastiness in not recognizing the film’s obvious value. It played a record 13-week engagement at Hollywood’s Hawaii Theater and by the end of its general nationwide release, had earned enough money to bring RKO back from the dead. Most available estimates credit an international gross exceeding $4,000,000.

Suddenly Lewton and Tourneur were the critics’ darlings and the talk of RKO. The esteemed film critic Manny Farber called Cat People "the best Hollywood film in three years.” Tourneur was given a bonus and a contract provision enabling him to go onto "A” pictures as soon as he finished his third Lewton film (by now already in production). Lewton’s meager $250-a-week salary remained just as it was, however.

[…] In today’s horror film climate, Cat People may seem like a tame and surprisingly ordinary film, but its approach was incredibly daring for its era. By design, Cat People was made to appear ordinary; Tourneur’s understated direction makes the film feel commonplace and uneventful, but underneath the apparent calm, the veneer of normalcy, run numerous sinister undercurrents.

Cat People has its share of flaws. Its ending is rushed and contrived, and a few scenes are difficult to swallow. The numerous meetings with Dr. Judd in the last half hour tax the viewer’s patience, especially when it should appear plain to any sensible human being that aside from being a probable quack, Judd is both a nuisance and a nemesis. The drafting office scene is effectively lit, but for such a climactic moment, it is curiously unsatisfying. The T-square business is such a horror cliché that for a moment we feel we are in the middle of a Universal vampire opus.

For all of its shortcomings, however, Cat People still works wonderfully well, never seeming like the cheap exploitation film that RKO intended it to be (judging from the studio’s misleadingly lurid newspaper ads and lobby posters). Instead, we get a well-conceived and carefully produced little film, one which possesses enough ambition to ably transcend its budgetary limitations. Lewton’s fear-the-dark approach—drawing equal measures of inspiration from Victorian ghost stories and Depression-era radio plays—struck a primal chord of fear with audiences across the nation.

It is remarkable how much care was given to the film, considering it was shot within three weeks and brought in under budget. Notice the amount of attention given to, the weather; we get sun, wind, rain, snow, and fog. Unlike the standard "B” budget programmer (which was usually designed for the 11 shirt sleeve” crowd), Lewton’s film strives to be artistic; as a result, it is loaded with provocative images — swords, keys, doors, walls, cages, staircases, water, birds, felines, and so on. Belying its modest budget, the film has an unusually rich sound track; Roy Webb’s score is very effective, never obtrusive. And yet so many memorable scenes rely upon silence punctuated with haunting sound effects: the clicking of high heels, the distant noises of zoo animals, the echoes in the swimming pool, and the hissing of air brakes. Mark Robson’s experience with the former boy wonder of radio, Orson Welles, is at least partly responsible for the peerless execution of the sound editing in Cat People. Many fans of the Lewton films credit the invention of the "Lewton bus” to Jacques Tourneur, but it was actually Mark Robson’s contribution. In The Celluloid Muse, Robson told authors Charles Higham and Joel Greenberg:

"The "bus” [was] an editing device I had invented by accident, or possibly by design. I put a big, solid sound of air brakes on it, cutting it in at the decisive moment so that it knocked viewers out of their seats. This became the "bus,” and we used the same principle in every film.”

Another significant way that Cat People defied genre conventions was its inclusion of so many ambiguous characters. Irena is not the only predator on the loose in this film; she is just the only one with any real sense of conscience. Like Larry Talbot in The Wolf Man or Countess Zaleska in Dracula’s Daughter, Irena doesn’t want to be a murderer; she just can’t help herself. Her prized statue of King John impaling a cat and her drawings of panthers vanquished with swords show how much she wishes to defeat her dreaded curse. She is a female version of the classic noir protagonist: obsessed, alienated, haunted, ill-advised, and doomed. So strongly do we sympathize with Irena’s agonized plight that we forgive her for her actions, even for something as questionable as feeding a dead canary to a panther. Irena remains the character for whom we feel the most genuine concern, even after we know how dangerous she has become. The RKO poster art may characterize Simone Simon’s character as the ultimate female predator, but she is really the film’s ultimate victim, the only one for whom we will finally grieve.

Each of the secondary characters, Oliver, Alice, Judd, exhibits questionable motives and behavior. Oliver Reed is appealing at first, but the more we see, the less we like. Halfway through the film, Oliver admits to Alice that until he married Irena, he had "never known the meaning of unhappiness.” He is a callow, overgrown boy who is used to having his own way. Oliver aggressively goes after Irena, getting everything he sets his sights upon. He hounds Irena into marriage, barreling his way through all her fears, calling them superstitious nonsense, and somehow manages to have her put aside a lifetime of self-doubt to agree to become his wife. The only thing he cannot get Irena to go along with is having sex.

Oliver is a draftsman, a designer, a man who likes to build things. He may be something of a square, but he is just the sort of square society seems to like, stiff upper lip and all that. He seems to take all his meals in restaurants, and he is forever being served apple pie (the waitresses know him well and deliver this dessert before he puts in his order). Imagination to Oliver is a tool for work, something to be left behind at the office. For all his expertise at his job, he seems a dullard around the house, never doing much besides putting a new mast on his model boat or pacing around Irena’s apartment pretending to be patient. He may be a survivor, but we should not rule out the "blind luck of fools” as a considerable portion of Oliver’s survival gear. Kent Smith may have been a limited actor, but his performance in Cat People, often.denounced as wooden and bland, is misunderstood primarily because audiences expected something more rousing from the all-American hero Oliver Reed appeared to be. He looks like a hero, so he must act like a hero, and because Oliver’s ambiguous character falls short of being heroic, Smith’s "bland acting” is often blamed. But Oliver, as written, is a stalwart, shallow, and self-serving character who is only posing as a film hero.

Jane Randolph’s Alice, with whom Oliver shares an "above-board” relationship, is an equally ambiguous character. Alice professes a tremendous concern for Oliver and Irena and appears to be (thanks to Oliver’s candid dayby-day reports) quite an authority on the history of Oliver’s failed marriage. Alice seems to encourage Oliver’s marriage, but her various "slips” in front of Irena seem deliberate, and the conspicuous time she spends with another woman’s husband outside of work is at best reckless and insensitive, given the situation. Unless Alice is plain stupid (which is obviously not the case), she is entirely aware of the way she is undermining Oliver’s marriage. Alice is clever enough to know what she is doing, and Oliver doesn’t just happen to fall in love with her. One of her tactics —shedding tears when Oliver confesses unhappiness—is older than Greek drama.

Lewton and Bodeen were able to undermine the appeal of Oliver and Alice with such subtlety that one can easily, upon first glance, mistake them for admirable human beings. But, as Oliver remarked earlier, one never ceases "to marvel at what lies behind a brownstone front.”

Although no viewer mourns his passing, Judd provides a distinct purpose; he is the voice of reason, the debunker of superstition. But when we have someone this unlikeable speaking on behalf of reason, the audience feels inclined to refute logic and accept the supernatural instead. When Judd makes jokes about silver bullets, it only makes the viewer wish to see him be attacked by a werebeast all the sooner. By making Judd such a disreputable authority, Lewton and Bodeen have provided a voice of reason with no credibility.

J.P. Telotte, in his volume on Lewton, Dreams of Darkness, points out an intriguing facet of the "normal” characters in Cat People: none of them have homes of their own. It’s true. Irena’s apartment is the only example of personal "living quarters” in the entire film, and yet, being a foreigner who can’t forget her origins, Irena is the character who is farthest from her home. Alice takes a room at the YWCA, but we never see it. Dr. Judd lives in a hotel room (which we never see) when he’s not at his office. And Oliver’s home (prior to his moving in with Irena) remains an absolute mystery.

It is true that Cat People owes a debt to The Wolf Man, and it is probable that many members of the Lewton unit had seen Waggner’s film. (By the time Cat People went into production, The Wolf Man’s screenwriter, Curt Siodmak, had already been secured for the scripting chores of I Walked with a Zombie.) Irena’s lullaby has the same old-world effect as The Wolf Man’s gypsy verse ("Even a man who is pure at heart…”) and the love triangle in the Waggner film is uncomfortably similar to the romantic triangle in Cat People (though the genders are reversed). Larry Talbot’s pursuit of Evelyn Ankers also exhibits the same blindly aggressive drive we see in Oliver’s whirlwind courtship of Irena; neither of these stereotypical All-American males will take no for an answer.

Cat People may have lost some of its edge over the years and what remains may be a bit tarnished, but it is infinitely better than Paul Schrader’s 1982 remake. […] It was Lewton’s film that became a national phenomenon, its simplicity and subtlety delivering an impact that Schrader, even with his top notch cast and expensive effects, could not come close to repeating. Three years later, in a Life magazine interview (Feb. 25, 1946), Lewton aptly expressed the reason for his success when he said:

"I’ll tell you a secret: if you make the screen dark enough, the mind’s eye will read anything into it they want! We’re great ones for dark patches. … The horror addicts will populate the darkness with more horrors than all the horror writers in Hollywood could think of.”

Edmund G. Bansak: Fearing the Dark. The Val Lewton Career.

Jefferson/N.C.-London 1995, S. 121-129, 136-140

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

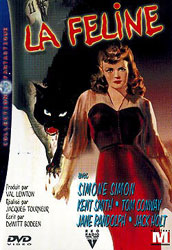

DVD

|

La Féline

FilmOffice / Editions Montparnasse

Collection Fantastique, #6

|

| Runtime: |

72:28 min (= 75 min PAL) |

| Video: |

1.30:1/4:3 Fullscreen

|

| Bitrate: |

6.20 mb/s

|

| Audio: |

English Dolby Digital 1.0 Mono

|

| Subtitles: |

Français

|

| Features: |

Extraits de films de la collection: Angoisse, La chose, L'homme léopard, L'invasion des profanateurs de sépultures, King Kong, La malédiction des hommes-chats, Le récupérateur de cadavres, Vaudou (07:13 min)

|

| DVD-Release: |

18 October 2000 |

|

Chapters: 12

Keep Case

DVD Encoding: PAL Region 2 (France)

SS-SL/DVD-5 |

Image: Le master utilisé est partiellement abîmé [...]. On n’est ainsi pas surpris de voir quelques griffures sur la copie [...] et de nombreuses poussières. Heureusement, la définition est exemplaire et le noir et blanc a de la gueule. Mais une fois encore, la compression joue des tours et ne permet pas à l’image d’échapper au côté froid du numérique. De plus, on note certaines bizarreries comme cette image qui se fige durant quelques secondes vers la demi-heure du film.

Son: [...] Même si le souffle n’est pas trop prononcé, il est quasiment toujours présent gâchant forcément un peu le spectacle. Dommage car sinon, le mono s’avère être d’une belle ampleur et certains effets pourront même en faire sursauter quelques uns (l’arrivée impromptu du bus notamment).

Interactivité: [...] les éditions Montparnasse n’ont pu proposer de bonus si ce n’est des extraits des autres films de la collection. En revanche, l’éditeur a soigné le menu de présentation avec une musique pour le moins stressante.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg) |

|

|

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)