|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

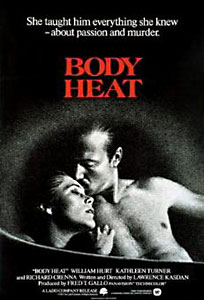

Body Heat

(Body Heat — Eine heißkalte Frau / Heißblütig — Kaltblütig |

La fièvre au corps)

|

|

|

| |

|

USA 1981 | 113 min

Director: Lawrence Kasdan

Producer: Fred T. Gallo, Lawrence Kasdan

Executive Producer: George Lucas (uncredited)

Production Company: The Ladd Company for Warner Bros.

Screenplay: Lawrence Kasdan

Cinematographer: Richard H. Kline, A.S.C. (Technicolor, 1.78:1 WideScreen 35mm)

Editor: Carol Littleton

Music Score: John Barry

Sound: David Sanucci, James Cook

Production Design: Bill Kenney

Set Decoration: Rick T. Gentz, Richard McKenzie, Sig Tingloff

Costumes: Renie Conley

Location: Hollywood / Lake Worth, Florida / Haena, Kauai, Hawaii

Cast: William Hurt (Ned Racine), Kathleen Turner (Matty Walker), Richard Crenna (Edmund Walker), Ted Danson (Peter Lowenstein), J.A. Preston (Oscar Grace), Mickey Rourke (Teddy Lewis), Kim Zimmer (Mary Ann Simpson)

Premiere: Aug 1981 (USA) | 19 Feb 1982 (Germany)

|

|

|

International Movie Database International Movie Database |

All-Movie Guide All-Movie Guide |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

"You're not too smart," Kathleen Turner's spider, Matty Walker, tells fly-to-be Ned Racine (William Hurt) on their first meeting. "I like that in a man." Married to a wealthy, older land speculator (Richard Crenna), Matty has other plans for her life, plans which the insurance on her husband's head would just about finance, and which Ned's immediate, obsessive fix on her will just about facilitate. Sound familiar? Body Heat is that rare thing, a remake that works-on its own terms. Double Indemnity with a twist of Postman coming to haunt us from Out of the Past: Body Heat makes no bones about its debt to the forties noir, a genre which it both replicates and caricatures. Hurt's smalltown Florida lawyer is too simple to be either classy or crooked; he's the perfect foil for Turner's displaced midwestern teenager hiding out in a grown woman's groans. The critics along with Ned fell for all that sweat and heavy breathing but the beauty of Turner's first major film performance is the way it presages the cannily tongue-in-cheek passions of Prizzi's Honor and Romancing the Stone; the beauty of William Hurt's Ned that he recognizes his own soft-spoken nothingness; and the beauty of Body Heat that its fatal passions-like those of James M. Cain's victims-are so very personal, enormous only in comparison to the God-forsaken corner in which they were spawned.

Body Heat is the earliest and perhaps best example of neo-noir films that directly confront the love/sex, honor/money dichotomies. A less-than-average lawyer gets involved with a rich man's wife and, despite clear warnings from both law-enforcement and criminal associates, develops a scheme to murder her husband. Lawrence Kasdan's script has as many twists and tums as the most complicated classic period narrative, but his male protagonist is emotionally closer to Steve Thompson in Criss Cross than Walter Neff in Double Indemnity. That leaves him vulnerable to the ultimate double-cross by an 80's femme fatale more cunning than most of her antecedents. Kasdan uses unexpected detail, such as the wind-chimes in the early conversation on the porch or the dancing prosecutor, to distract both viewer and protagonist from the sordidness of the underlying reality. Because the viewer co-experiences his betrayal, Body Heat evokes the noir sensibility much more powerfully than many of the films which followed it.

Film Noir. An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style

Woodstock NY 1992, p. 400

Hot and sticky, though never less than sumptuously deodorised, this is a neon-shaded contemporary noir romance: all lust, greed, murder, duplicity and betrayal. As credulously myopic lawyer Ned and slinky femme fatale Matty progress from dirty talk to dirty deeds (a disposable husband, a contestable will), there's the pleasure of unravelling a confidently dense yarn for its own sake, alongside the incongruous experience of finding yellowing pulp fiction classily rebound, or hearing a '40s standard of romantic unease re-recorded with digital precision. Whether the movie-movie cleverness becomes as stifling as the atmosphere Kasdan casts over his sunstruck night people is all down to personal taste, but there's no denying the narrative confidence that brings the film to its unfashionably certain double-whammy conclusion.

Excellent, if slightly calculated, crime drama in the fashion of Chandler, Cain, and Hammett. Writer-director Kasdan borrows liberally from the aforementioned in his style and substance. The plot is quite close to Double Indemnity in that it's the woman who plans knocking off her husband and enlists an unwitting, somewhat simple man as her accomplice. The major difference between this film and the film noir of the 1940s is that Kasdan has included steamy double entendres more in keeping with contemporary movies. [...]

Turner was a sizzling sensation in her screen debut, making her character one of the '80s most memorable femme fatales, a cool, calculating woman whose torrid love scenes with Hurt are terrific. For his part, Hurt, in his third film, is perfectly convincing as the low-rent attorney who gets in way over his head, though one does have to wonder just how this guy ever got a law degree. Though he's only on screen briefly, Mickey Rourke is mesmerizing as one of Hurt's criminal clients, showing the charisma that would soon shoot him to stardom. All of the secondary roles, in fact, are well cast and well performed. Every detail of the technical credits is also first-rate, making this one of the best mysteries to come out of Hollywood since Chinatown.

Body Heat ist der erste Spielfilm von Lawrence Kasdan, der zuvor als Drehbuchautor für George Lucas (The Empire Strikes Back / Star Wars II - Das Imperium schlägt zurück, 1980) und Steven Spielberg (Raiders of the Lost Ark / Jäger des verlorenen Schatzes, 1981) tätig war. So brillant kalkuliert und spektakulär, wie in diesen Filmen Genregrenzen überschritten und Genrespezifika übersteigert werden in einem Wirbel von Zitaten, so treffsicher schreibt und inszeniert Kasdan in seinem Debüt einen Klassiker des Film noir um: Billy Wilders Double Indemnity (Frau ohne Gewissen, 1944). Bei Kasdan wird Wilders kühl-zynische Variation des Geschlechterkampfes auf paradoxe Weise sinnlich überhitzt und zugleich abgekühlt. Das schwüle Florida ist ein Treibhaus der Leidenschaften und der Gier. Body Heat spielt überwiegend nachts, und in der vor Hitze flirrenden Dunkelheit löst sich soziale Realität so auf wie das Zeitgefühl. Matty, die Femme fatale, zieht den mediokren Ned Racine, dem Kasdan als ironisch-bitteren Kontrast einen zu Assoziationen verführenden Nachnamen gibt, in diesen Rausch der Auflösung hinein, der zugleich ein von ihr kalt geplanter und gestalteter ist. Das Gleiten von Neds Hand über ihren seidenen Slip, die schwitzenden Körper auf Satinlaken, die die Kamera abtastet, visualisieren nicht allein Neds sinnliche Erfahrung eines endlich gelebten Traums, sondern vor allem, dass Matty, die Frau mit vielen Identitäten, ihm diesen Traum erfüllt, um die libidinöse Energie umzupolen auf Mord. Mattys Spiel mit Ned ironisiert Kasdan aber auch, wenn sie Ned einen klassischen Bogart-Hut schenkt, den der mit wenig Erfolg so elegant wie das Vorbild auf den Hutständer zu werfen versucht. Die Frau, die für ihn die Erfüllung aller Projektionen begehrenswerter, verführerischer Weiblichkeit ist, macht ihn ihrerseits zu einem Trugbild harter Männlichkeit. Aus dieser Identifikation mit dem Simulakrum heraus handelt Ned. — Kasdans Inszenierung ist so eine der Verdopplungen, eine der wiederholten Spiegelungen, die gebrochen werden.

Die Film-noir-Story, die auch James M. Cains Roman "The Postman Always Rings Twice" und dessen Verfilmungen (Visconti / Tay Garnett) zitiert, wird von Kasdan derart strukturiert, dass sich aus der Eleganz der Bildkomposition und der Intertextualität filmischer Verweise ein Mechanismus des Spiels ergibt, das den Zuschauer zum bewusst eingeplanten "Bestandteil des ästhetischen Effekts" macht (Jameson). Welche Position Ned in diesem Spiel einnimmt, wird schon früh musikalisch klar. Als er bei Teddy Lewis (Mickey Rourke in einer seiner ersten Rollen) die Brandbombe abholt, dröhnt laut Bob Segers Song "Feel like a Number", den Ned genervt abstellt. Er ist selbst nur eine Nummer, nur ein Zitat eines "tough guy". Kasdan geht sogar so weit, in einer Szene nahe zu legen, alles sei ein Spiel von Matty und Walker, um Ned auszutricksen. Bevor Ned in das Haus der Walkers eindringt, steht Edmund Walker auf und sagt zu Matty: "Es reicht, wenn einer von uns nervös ist." — Diese Szene, eine bewusste Irreführung des Zuschauers, verstärkt jedoch nur den Eindruck, dass Ned, der gesteuerte Mann, wie auch immer, chancenlos ist.

Bezahlten bei Wilder und in Cains Roman die Frauen ihr gefährliches Spiel mit dem Leben, so kommt bei Kasdan die Frau mit der Beute davon, da sie klüger und gerissener ist als alle Männer. Doch dieser Sieg ist der einer eiskalten Begehrlichkeit nach Geld. Matty, die nicht Matty ist, tritt in ihren weißen Kleidern als Verkörperung vorgetäuschter Unschuld in die heiße und feuchte Nacht von Neds Männerphantasien. Sie hat von ihrem Mann, der dubiose Geschäfte betreibt, gelernt: "Man muß tun, was man tun muß." Entscheidend ist, was man erwirbt, nicht, wie man es erwirbt. So wird Ned nicht das Opfer einer Frau, sondern das eines Prinzips — der kalten Berechnung einer Bereicherungsgesellschaft, an der er gerne teilhätte, die aber Figuren wie ihn nur benutzt. Unschuldig ist bei Kasdan niemand. So treibt Body Heat das postmoderne Vexier- und Zitatenspiel bis dicht heran an die Logik der amerikanischen Gesellschaft. Prinzipien — wie die des Rechts — verkehren sich in ihr Gegenteil, und hinter Leidenschaft verbirgt sich Gier nach Geld. So ist die Hitze in Body Heat nur simuliert. Entscheidend ist die Kälte der Verhältnisse, die die Körper und ihre Wünsche prägen. Pauline Kael schrieb über den Film: "The lovers sweat constantly [...]. But it might as well be dew." - Die Liebenden schwitzen ständig, doch es könnte auch Tau sein.

Bernd Kiefer, Reclams elektronisches Filmlexikon

sex and identity

Are you who you really say you are? Are you living under an assumed identity? Such identity masking is usually the cover-up for a crime, but in Body Heat it's the prelude to a crime. Yet the question of identity goes well beyond such maudlin pursuits as greed and fast money. The architecture of fantasy is sex. And the femme fatale is the architect.

Ned Racine (Hurt) is a thirty something lawyer working the seedy side of the street in Miranda Beach, Florida. You first see him standing on a small balcony looking at a column of fire in the distance as a casual lover dresses and banters in the room behind. He's naked from the waist up, his slender body sweating from the tropical heat. He assumes the fire is arson, a real-estate swindle. "History is burning up out here," he says, and you sense that he is the cynical post-modern replacement... even if his Creole name and the fact that he grew up here suggests otherwise.

Racine is presented not so much as careless as casual. As a single male, his slow talking sensuality and hip cynicism mark him as a man whose first priority is sex, his second, business. While he's a womanizer, you don't get the feeling that he's an abuser or a crook. He's just an opportunist, a drifter in search of something he has yet to define. "Next time you come into my courtroom, I hope you've got a better defense... or a better class of client," says the Judge in his reprimand. So perhaps when Racine encounters Matty (Turner) that evening at the concert down on the beach, he's following the Judge's advice, moving up from his waitresses and female cops into a higher class of lover.

And who would think that this encounter was anything other than chance? As usual, it's lust at first sight. An elegant woman in summer white leaves her seat near the stage, walks slowly towards where he stands on the boardwalk overlooking the beach. She pauses for air, leans on the railing. He moves in swiftly like the hustler he is. Their exchange is bold, the innuendo sexual. "I'm a married woman," she says. "You didn't say happily married woman," he says. He quickly intuits that she's from the upscale Pinehaven neighbourhood and just as quickly seems to be in control of the situation. He buys her a Cherry float... she spills it on her dress. He takes the cup from her, heads for the can to dump it. "Don't you want to lick it?" she says.

When he returns, she's gone.

Matty is a woman on the nub of discontent. The grass widow of a shady businessman who only comes home on the weekend, her elegant body unmarred by children or bad diet, her restlessness is the classic signature of the neglected woman. Or so it seems to Ned as he hunts her down in Pinehaven and begins a raunchy affair under the chimes that move softly in the sea air, seem to represent the mystery of this exciting woman. They screw here, they screw there, they screw like humans, they screw like animals... and so how long can it be before they're scheming to get rid of her husband?

"He's small... and mean... and weak," says Matty. Later, as they lie on the beach under the stars, she says, "I'm afraid... because when I think about it, I wish he'd die." And Ned, greedy and pussy-whipped, says, "It's what we both want."

noir, sex and the totemic woman

Matty's manipulation of events is standard for the film noir genre, of which Body Heat is the redefining drama of the post black and white era. At first you think of Double Indemnity as its ideological model, but in many ways Body Heat is closer to Hitchcock's transitional noir masterpiece Vertigo, as Matty Walker's deception uses masquerade as a form of totemic sexual hypnosis. Like Hitchcock's detective, Kasdan's Ned Racine is pursuing a woman who is masquerading as an ideal when in fact she is anything but. The similarity is also atmospheric, as John Barry's beautiful score is clearly in the dream sonata tradition of Bernard Herrmann's Vertigo theme. There are differences, of course, the main one being that Hitchcock's fatale (Kim Novak) is the agent of another man while Matty is strictly the author of her own agenda. In this regard, she is like Phyllis Dietrichson in Double Indemnity.

It's Matty who insinuates the problem, then suggests the solution even though Ned thinks the solution is his. While the death-fight with Edmund Walker in the hall of his opulent home is a fitting parody of Ned's first sex with Matty, the disposal of his body by arson bomb in the abandoned beachfront club The Breakers is sublime. The method is crude, yet the desired insinuation is that Walker died as part of an on-going real-estate scam engineered by the shadowy criminal investors with whom he's associated.

Yet even Teddy (Rourke) the bomb maker and client warns Ned against this audacious act. "Don't do it," says Teddy.

Cut To: a slow pan along Matty's legs, ass, naked reclining body. "Don't do it...." Sure. "Next time I see you," says Ned to Matty, "he'll be dead."

As per all film noir, the woman's patsy must be an expert. What's interesting about Body Heat is that Ned Racine is chosen not only because he's an expert but also a fuckup. The criminal rewriting of Edmund Walker's will requires an expert, of course, but also one who might make the mistake essential for Matty's plan to be fully realized. For the perfect crime, perfection must interact with its silhouette, imperfection. So it is that Ned thinks he's a partner in the grand deception when in reality he's merely a part.

Yet... why doesn't he recognize this before it's too late?

When an accidental encounter with Matty and her husband at a local restaurant turns into wine, dinner and conversation, you recognize that Ned is perhaps a junior version of Edmund. "I was a lawyer," says Edmund. "Don't practice anymore." Edmund goes on to mock the man Matty was with before they got married. "You wouldn't believe the dork she was with," he says. "Tries to make it with one score... but can't do what's necessary." Ned nods slowly, says, "Yeah, I know that kinda guy... I hate that kind." Then he smiles, adds, "I'm a lot like that." Both men laugh but neither, in fact, recognizes the true extent of their tragic symbiosis.

The police know that Edmund Walker was murdered and Racine knows they know, as he's a buddy of Lowenstein, the Assistant D.A. (Danson), and Oscar (Preston), the investigating cop. He's warned to stay away from Matty but, convinced that he has what it takes "to do what's necessary", he boldly continues his affair with the new widow — after all, she is his client. But when he discovers that she tampered with the will that he forged in such a way that the mistake makes her the sole heir of her husband's estate, he's so whipped he fails to see the fall before it happens. "I love you," she says... and she bought him a fedora, didn't she? Here the director Kasdan makes a sly allusion to the blind love chump Walter Neff in Double Indemnity, another "expert" with a fedora.

During the affair, certain incidents threaten to spoil their idyllic repose. Ned and Matty are caught in a sexual act by Heather, Matty's young niece... but when the critical moment comes, the niece fails to identify the man with the erection. More significant is the disappearance of Edmund Walker's glasses, which later factor as blackmail and the setup for Racine's elimination. Vaguely symbolic, Walker's glasses become both the talisman of death and male myopia.

As the story plot is synonymous with Matty's plot and this plot is both complex and sophisticated, understanding just what happens and how it affects Racine's disintegration isn't always easy. For example, you know that while Racine screwed up a previous will (the Gurson case) you wonder if in fact he screwed up the Edmund Walker forgery or if the devious Matty tampered with it to play on Racine's history of incompetence. Her admission, when it comes, can slip past you in the heat. Either way, of course, Edmund Walker's will becomes invalid and in the State of Florida "in testate" means the widow gets everything.

Part of the will deposition is the "missing witness" factor, which also figures significantly in the action and the crunching ironies of the ending. The witness is Matty's friend Mary Anne Simpson, now absent, supposedly on holiday in Europe. Somewhere in here Mary Ann is supposedly murdered by Matty and her body stashed in the boathouse in anticipation of her lover Racine's death by boobytrap bomb — the same type as Racine used to dispose of Edmund Walker. While the symmetry is neat, you wonder why Matty would use Racine's friend and client Teddy to supply the information for such an act... after all, Teddy picks up the phone and calls Racine... so Racine expects the boathouse to be boobytrapped.

Matty has shown herself to be smarter than that. But in the arcane movement of the final sequences, you might overlook such plot conveniences, marvel instead at the sweet irony.

clairvoyance, symmetry and the femme fatale

Incarcerated for two murders, Racine has a moment of clairvoyance, knows instinctively that Matty is still alive. His friend Oscar, the black cop, visits him in prison. "Her teeth, man," Oscar says by way of incontrovertible evidence that Matty died in the boathouse explosion. But Racine has it figured out: Matty is a masquerade. She has switched identities with her high school friend and is really Mary Ann Simpson. So naturally Matty (Walker) Tyler's teeth are found. "Matty sees a way to get rid of us both at once... two killers, dead."

The symmetry is indeed a thing of beauty — just like the fatal allure of the femme fatale herself. This symmetry forms the visual logic of the climactic scene, in fact. As Matty a.k.a. Mary Ann stops on the grassy fairway near the boathouse you see Racine in the distance and beyond him Oscar the cop, the three characters arranged like markers on a moral map. Matty is wearing the same close-fitting white dress she had on the first night she and Racine met. She stops, isolated like a white flame in the darkness. "Whatever happens," she calls. "You must believe that I love you."

Relentless? A person who could do whatever was necessary? Better believe it.

The performances in Body Heat are superb, from the principals to the secondaries. Ted Danson as the friend and Assistant D.A. who lives vicariously off Racine's sexual exploits and whose nature is so whimsical that he dances across parking lots and piers as one might doodle is a classic example of movie minimalism and the art of characterization. But Hurt and Turner as the reckless lovers are a thing apart, beautiful and crude, sexed and unhinged, just like their generation.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

DVD

|

Warner Home Video

|

|

Runtime:

|

108:36 min (= 113 min PAL)

|

|

Video:

|

1.76:1/16:9 Anamorphic Widescreen

|

|

Bitrate:

|

5.60 mb/s

|

|

Audio:

|

English Dolby Digital 5.1 Surround

Deutsch Dolby Digital 1.0 Mono

Español Dolby Digital 1.0 Mono

|

|

Subtitles:

|

English, Deutsch, Español, Français, Italiano, Turkish, Nederlands, Svenska, Norsk, Dansk, Suomi, Português, Hebrew, Polski, Hellênika, Ceské, Magyar, Íslenska, Hrvatski, Deutsch (captions), English (captions)

|

|

Features:

|

• US Theatrical Trailer (01:35 min)

• Cast & Crew Bio-/Fimographies

• Production Notes Behind-the-Scenes

|

|

DVD-Release:

|

25 September 1998

|

|

Chapter: 30

Snap Case

DVD Encoding: PAL Region 2 (Deutschland)

SS-SL/DVD-5

|

Das Bild wirkt leicht diesig, in dunklen Szenen jedoch recht kontrastreich. Scharfe Kanten sind rau. Kleine Artefakte in ruhigen Szenen.

Die Surrounds bleiben in der 5.1-Version ohne hörbares Signal. Die Ortbarkeit ist unklar, so daß der deutsche Mono-Track ehrlicher wirkt.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg) |

|

|

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)