![]() ChiaroScuro presents

ChiaroScuro presents

![]() ChiaroScuro presents

ChiaroScuro presents

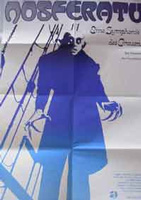

Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens

(Nosferatu – a Symphony of Horror)

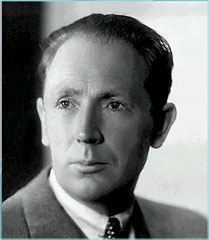

by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau

Germany 1922

|

|

|

|

Director:

|

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau | |

|

Producer:

|

Albin Grau, Enrico Dieckmann | |

|

Production Companies:

|

Prana-Film GmbH, Berlin | |

|

Screenplay:

|

Henrik Galeen (based on the novel "Dracula" by Bram Stoker) | |

|

Cinematographer:

|

Fritz Arno Wagner, Günther Krampf (b/w, tinted, 1.33:1) | |

|

Music Score:

|

Hans Erdmann | |

|

Art Director:

|

Albin Grau | |

|

Costumes:

|

Albin Grau | |

|

Cast:

|

Max Schreck (Graf Orlok / Nosferatu), Gustav von Wangenheim (Hutter), Greta Schröder (Ellen Hutter), Ruth Landshoff (Lucy Westrenka), Alexander Granach (Knock Makler), G.H. Schnell (Harding) | |

|

Runtime:

|

1970 m (94 min at 18 frames/sec, restored Bologna version) | |

|

Filming Location:

|

Studio: Jofa-Atelier Berlin-Johannisthal Outdoors: Wismar, Lübeck (Salzspeicher), Lauenburg, Rostock, Helgoland, Schloss Oravsky (Karpaten), Dolin Kubin auf dem Vratna-Paß, Schlesische Hütte, auf dem Fluß Waag, Tegeler Forst Production Dates: August - October 1921 |

|

|

Premiere:

|

Nosferatu. Eine Symphonie des Grauens Nosferatu le Vampire [First French Version] Nosferatu le Vampire [Second French Version] Die zwölfte Stunde. Eine Nacht des Grauens. [non-authorized re-adaptation of Murnau's film with newly shot scenes by Dr. Waldemar Roger] |

|

|

On the Way to Nosferatu

by Enno Patalas ("Unterwegs zu Nosferatu. Vorstellung einer Rekonstruktion", in: Filmblatt, No. 18, 7/2002) |

Murnau's Nosferatu was never a 'lost film'. Unlike Der Gang in die Nacht (Journey into the Night), Phantom, Die Finanzen des Großherzogs (The Finances of the Grand- Duke) and Der brennende Acker (Burning Earth), Nosferatu has always been with us, in various different forms. This is largely thanks to Henri Langlois and the Cinémathèque Française, who preserved a copy of the second French version, dated 1926 or 1927. This version contained the famous title which had so delighted Breton: "Et quand il fut de l'autre côté du pont, les fantômes vinrent à sa rencontre" - which could be seen as an admittedly free but by no means inappropriate translation of the original German text: "Kaum hatte Hutter die Brücke überschritten, da ergriffen ihn die unheimlichen Gesichte..."

It was a print from this version that reached the New York Museum of Modern Art in 1947. There, as was the norm in Iris Barry's time, the foreign-language intertitles were translated into English. In the process, the names of the characters (which in the French version had roughly approximated to the German names) were changed to the names of the characters in Bram Stoker's Dracula, which the film is of course based on. In this it followed the first American version of the film. Orlok thus became Dracula, Hutter became Jonathan Harker, Knock (who had been Knox in the French version)- Renfield, Bulwer - Van Helsing..., and Wisborg became Bremen. This is the form in which the film returned to Europe, firstly to London and the National Film Archive and thence to Germany, to a distribution company which was, in the '60s, performing a valuable role in making 'Weimar cinema' available to a wider public. This company translated the English titles back into German, retaining the altered names. (When copies were needed for export into francophone countries they translated the German titles - which had been translated from the English titles, which themselves had been translated from the French - back into French. The film is still shown in this form in Goethe Institutes in Montreal, Brussels, Toulouse and Paris. The descriptions of the film to be found in issue no. 228, 1979, of l'Avant-Scène/Cinéma and in Bouvier-Leutrat's 1981 book are also based on this version.)  At the same time the graphic form of the intertitles was standardised from one version to the next, and there was a loss in image quality down the generations. There is a story - I do not know whether it is true - that Henri Langlois used to remove the intertitles from prints of silent films. What is certain is that he was not very interested in preserving or restoring them. This was in marked contrast to Lotte Eisner, who was aware of the importance of titles - at least in German films of the '20s - and who inspired me, 20 years ago, to begin searching for the titles of Der müde Tod (Destiny) and also Nosferatu, which were thought lost. The evidence of the script and title-list from Murnau's estate, which Lotte had secured for the Cinémathèque Française - and which are reproduced in facsimile in the appendix to the German edition of her book on Murnau - suggested that such a search might be worthwhile. From them we discovered that in the known prints, of French provenance, a sixth of the intertitles were missing (16 out of the original 97, not counting the 19 act- and opening and closing credit-titles), and that many of the remaining titles differed greatly from the original text. We also discovered that writing in the film had originally had a far greater importance than the French version and its descendants had suggested.  This was true not only of Nosferatu but also of Caligari, The Golem and Fritz Lang's Der müde Tod and Dr. Mabuse. In the most important German films of the early '20s, intertitles served not only as headings and to convey dialogue. The Caligari titles, painted by Hermann Warm, are a continuation of the sets, also designed by Warm, while, working the other way round, painted words ("You must become Caligari!") suddenly appear in the sets. In Der müde Tod the graphic style of the intertitles (which I found as flash titles in a print in the Moscow archive) are related to the place, time and background story of the three episodes. The Golem titles bear the signature of the designer of the ghetto sets, Hans Poelzig. In Nosferatu the action was linked to three books: to the 'diary', a kind of chronicle of the plague, whence the action initially emerges and into which it finally returns; to, secondly, the vampire book that Hutter finds in the Carpathian inn - just as one might find a Bible in a hotel room today - which shows him and his wife their future; and, finally, to the ghost-ship's log book. In these books the action never simply moves on - rather the books edge what is seen and shown into a shadowy half-light - from both the characters' and the viewer's point of view. There are, in addition, letters, a page from a newspaper and various official documents. The well-known French version and those based on it ascribed the 'diary' to Johann Carvallius or Cavallius, "ancien magistrat et habile historien de sa ville natale". In Murnau's title-list, on the other hand, the keeper of the diary is anonymous, without fame or title. His signature is three crosses - "three properly painted graveyard crosses" are specified in the title-list - a voice from beyond the grave. This was obviously too irrational for whoever put together the French version. The greatest works of the German cinema of the early '20s almost without exception make reference to 'author-less' literary genres, traditional or modern - to anonymous testimonies and traditions, to folk tale, legend, books of magic, chronicles as well as crime novels and science fiction, but almost never to the work of well-known writers. Fritz Lang made no distinction between filming a story from a newspaper serial such as Dr. Mabuse or a saga like Die Nibelungen, and when Murnau was shooting his Faust he followed not Goethe but the medieval folk epic. The anonymity of the storyteller, his voice from beyond the grave, is not the only pointer in Nosferatu signalling the disintegration of the bourgeois author and the bourgeois hero. The story-teller who signs his work with three graveyard crosses matches the vampirical Count, who finally disappears in a puff of smoke, a creature somewhere between human and animal, between life and death, a hermaphrodite like the flesh-eating plant with which he is compared in the film. (And Ellen, in the first dialogue title of the film, talks of the flowers Hutter has picked for her as though they were living beings: "Why did you kill them?" she asks. Again, it is certainly no coincidence that this title is among those deleted in the French version.) It is therefore not a sign of inconsistency when Murnau, having used 116 intertitles in seven different forms in Nosferatu, then, inspired by Carl Mayer, followed the example of Scherben (Shattered) and Sylvester (New Year's Eve) and made Der letzte Mann (The Last Laugh) almost without titles, explaining that the ideal film is one without any intertitles whatsoever. The proliferation of non-literary, pre-literary, popular and anonymous forms of speech and writing already goes some way towards dissolving the link between cinema and literature, the most sustained expression of this effect being the title-less film which rests entirely on the image.  The significance of the intertitles of the Ur-Nosferatu is evidenced by the title-list, but is illustrated even more clearly in a print preserved in the Staatliche Filmarchiv der DDR (the GDR State Film Archive) which was made available to the Münchner Filmmuseum in 1980 for our first attempt at a reconstruction. Albin Grau, who was also responsible for the sets and costumes, had done the lettering. They are like shot set-ups within the film proper, and fade in and out. Pages are turned. This print from the GDR Archive was of course no more than a skeleton, but it did contain most of the titles and at least examples of almost all types of titles and inserts occurring in the film, credit and dialogue titles, the diary, the vampire book, the log book, letters, etc. Only the titles indicating start and end of acts were missing. This print enabled us, in the '80s, to make new prints of the titles, or to letter them ourselves in a faithful copy of the original, or to put together and then film the background elements with their text. Also in 1980 Mary Meerson made available to us another version of Nosferatu from the holdings of the Cinémathèque. It was again Lotte Eisner who had alerted the world to the existence of this version in an article for the January 1958 issue of Cahiers du Cinéma entitled L'Enigme des deux Nosferatu. It was about a version with the title Die zwölfte Stunde ('The Twelfth Hour'), which a certain Dr. Waldemar Roger had assembled in 1930 with the intention of releasing it with sound - not optical sound but 'stylus-sound', i.e. a combination of film and gramophone record. This version contained a series of additions, mostly designed to provide visual justification for the use of music. Many parts were changed around in order to give the film a happy ending, for example. Again and again sequences and single shots had been shortened. The intertitles were completely new and quite different. There are however long sections where this re-edit has obviously left the original shot sequence untouched. This provided us with several shots that we had previously known in either abbreviated versions or in poor condition or indeed had not known at all. These we could now add into the reconstruction. Intertitles are not the only aspect of '20s cinema which was neglected - if not actually despised - by the post-war generation of cinephiles: colour is another. They came to know and love the cinema of this era in the black-and-white prints via which it was handed down to them. This was, of course, in a period when the passage from blackand- white to colour was as controversial as the change from silent to sound film had been twenty years earlier. The Cinémathèque print of the second French version of Nosferatu was black-and-white, as were all the prints made from it as well as those preserved in East Berlin and also Die zwölfte Stunde. Nosferatu must have been in colour at the time of its release in 1922 - 'tinted' and perhaps also 'toned'. We make this assumption not only because this was normal in Germany at the time, but also because a vampire does not walk around in broad daylight, as he does in all the black-and-white prints of the film. A definite indication that Nosferatu was intended to be coloured was found in Act 5 of the film. In the shot where the wind blows a candle out, in this exact place, there was a splice, demonstrating that the sections before and after had been printed separately, the first to be coloured yellow or orange for candle-light and the second blue or green, for night and moonlight.  We do not know, unfortunately, how much influence Murnau exerted on the colouring of his films. I only remember one note, in his handwriting, in the script of Schloss Vogelöd (Castle Vogeloed), saying, "Leave the dream scenes black-and-white." (Strangely, the relevant page has in the meantime disappeared from the script preserved in the Bibliothèque du Film.) He obviously left the rest of the colouring to the laboratory staff making the prints. The original intertitles also indicate that Nosferatu was very much conceived as a day-and-night film. At the beginning of the film every change in the time of day is announced by a title ("... at last the Carpathian peaks lit up before him", "Hurry, the sun is setting!", "As soon as the sun rose, the terrors of the night left Hutter"), followed by a twilight image - a mountain view, clouds or seascapes, always without people. Later in the film the twilight images function alone, without introductory title, to mark the change from day to night and vice versa. In the mid-'80s Luciano Berriatua of the Filmoteca Española, an eminent Murnau scholar, found another print of Nosferatu in the depths of the Cinémathèque vaults, a print which even Lotte Eisner herself had obviously failed to find. It was a coloured copy of the first (1922) French version of the film (about which Robert Desnos had written long before Breton had noted the film). Parts of the film were missing, due to deliberate cuts by the distribution company as well as normal wear and tear on the print, and the colours had altered considerably - the blue of the night scenes had disappeared completely, and Nosferatu was again walking in the sunshine. Nevertheless, it was still possible to see which colour had been allocated to which section. We could also tell that the French distributor had - as was normal at the time - received the coloured positive print from Germany, producing only the French titles in France. One could therefore assume that the French version was based on the same colouring plan as the German version. This made it obvious that night scenes had sometimes been coloured blue and green, even when a lamp was visible as the light source and one would therefore have expected yellow. In the scene at the Carpathian inn in Act 1, blue exterior shots alternate with yellow interiors, as was the convention at the time, but in the scenes in Hutter and Ellen's apartment in the final act, when Nosferatu is sucking Ellen's blood, blue exteriors alternate with green interiors. Green, alternating with blue, underlines the eeriness of these scenes, which suggests that when Hitchcock was deciding on the colouring for The Lodger he remembered the music-hall melodramas he saw as a child, where the villain was always bathed in green light. Twilight images in Nosferatu were originally coloured pink as a rule with only one - the shot with the flesh-eating plant, the venus fly-trap - coloured orange. In 1994 the Cineteca del Comune di Bologna undertook, in the context of the European Community's Lumière Project, to continue the reconstruction which had begun in Munich. First a black-and-white negative was printed from the Paris colour print on to panchromatic stock. All missing, incomplete or damaged shots were replaced from the two other nitrate prints in the Cinémathèque Française, a nitrate dupe negative of the second French version and a nitrate positive print of Die zwölfte Stunde. A colour positive print was struck from this black-and-white negative using the method developed by Noël Desmet at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique: "A neutral blackand- white image is first struck from a black-and-white negative and printed on to a positive colour emulsion...; this image is then exposed, without negative, to the desired colour by flashing coloured light on to it. The result is a black-and-white image on a tinted background." In addition to the 522 shots of the well-known version - not including titles and inserts - a further thirty gradually found their way into the reconstruction. Most are single shots or, more rarely, two or three within a sequence. Only in one place is there a short sequence of five new shots together (in a scene with Harding and Ruth playing croquet). Other shots are now longer and fade in and out where there had previously been 'hard' cuts, or the image quality has been improved. An extra 400 metres has been added to the 1,562 metres of the well-known version, so that no more shots should now be missing from the original 1,967 metres length. Even more of a bête noire to old-school film-buffs than the colouring and toning of prints is the practice of presenting them with musical accompaniment. Henri Langlois was not, it seems, always dedicated to showing 'silent films' silent, and in the early days he would have Joseph Kosma accompany them on the piano. Certainly, musical accompaniments in the silent film era were normally an element in bringing a film to the people rather than a part of the film's artistic creation, and it took a new interest in this aspect of cinema history, a desire to look beyond auteur theory, to persuade film archives and cinémathèques to start concerning themselves with the music. There are however indications that directors such as Lang and Murnau were no more indifferent to the musical accompaniment than they were to the colour or indeed to any part of the technical aspect of their films. We discover from the title-list handed down by Lotte Eisner that the credits of the Ur-Nosferatu give Hans Erdmann as the composer of the original music for the film, just as the Nibelungen and Metropolis title-lists name Gottfried Huppertz. Erdmann was a conductor, composer and music critic and from 1926 edited the journal Film - Ton - Kunst ('Film - Sound - Art'). In 1927, together with Giuseppe Becce, he published the Handbuch der Film-Musik. In 1932 he wrote the music for Fritz Lang's Testament des Dr. Mabuse. Erdmann and Becce have reported that, before completing his films, Murnau used to discuss the music with the composers. Erdmann composed his Nosferatu score as a suite which he called Fantastisch-Romantische Suite. It was published in two arrangements, one for full orchestra and one for palm court orchestra. The score contains ten titles - Idyllic, Lyrical, Ghostly, Stormy, Destroyed, Strange, Grotesque, Unchained, Distraught. None of the ten pieces, wrote Erdmann in an open letter to an orchestra director who had attacked the composition as "too highbrow", was "planned in such a way that it must always be used in the form provided. It is of course possible to do so, but by no means obligatory." The suite was used in the cinemas of Berlin "with varying degrees of success. Sometimes very good effects were produced, but in other cases the results were less satisfactory." I finally heard this music, arranged by the Berlin musicologist Berndt Heller and played by the DEFA Symphony Orchestra (now called the Babelsberg Film Orchestra), during a presentation of the film in a church in Neu-Ruppin in the Brandenburg Marches. What struck both Heller and myself, completely independently, was how the musical and colouring effects reinforced each other.  |

|

|

Restoration:

|

• 1981: 1.733 m

Filmmuseum München: Enno Patalas, Klaus Volkmer, Gerhard Ullmann, supported by Cinémathèque Suisse, Cinémathèque Française and the Staatliche Filmarchiv East Germany. B/w. First screening: 5 June 1981, Cinémathèque Française A black-and-white print of the second French version of 1928 (Cinématèque Suisse) was completed by sequences taken from a nitroprint of the apocryphical version Die zwölfte Stunde ("The 12th Hour", Cinémathèque Française). New German intertitles and inserts according to the original title list, as printed in Lotte H. Eisner: F. W. Murnau, Paris 1964, and based on the graphical conception of a print from the Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR. (Enno Patalas) • 1984: 1.733 m • 1987: 1.910 m (= 92 min at 18 fps, better: 103 min at 16 fps) • 1995: 1.970 m (= 94 min at 18 fps) |

|

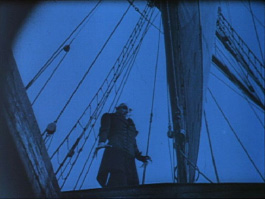

"... Nature participates in the action: sensitive editing makes the bounding waves foretell the approach of the varnpire, the imminence of the doom about to overtake the town. Over all these landscapes — dark hills, thick forests, skies of jagged storm-clouds — there hovers what Balazs calls the great shadow of the supernatural.

... The architecture in Nosferatu, typically Nordic — brick façades with stubby gables — is perfectly adapted to the film’s strange plot. Murnau did not have to distort the little Baltic townscapes with contrasting lighting effects: there was no need for him to increase the mystery of the alleyways and squares with an artificial chiaroscuro. Under Murnau’s direction the camera of Fritz Arno Wagner required no extraneous factors to evoke the bizarre. ... Murnau created an atmosphere of horror by a forward movement of the actors towards the camera. The hideous form of the vampire approaches with exasperating slowness, moving from the extreme depth of one shot towards another in which he suddenly becomes enormous. Murnau had a complete grasp of the visual power that can be won from editing, and the virtuosity with which he directs this succession of shots has real genius. Instead of presenting the whole approach as a gradual process, he cuts for a few seconds to the reactions of the terrified youth, returns to the approach, then cuts it off abruptly by having a door slammed in the face of the terrible apparition; and the sight of this door makes us catch our breath at the peril lurking behind it." — Lotte H. Eisner: The Haunted Screen. Expressionism in German Cinema. Berkely/Cal. 1973, pp. 97-105 "... Man hat Murnau zu Recht nachgerühmt und darin einen exemplarisch 'modernen' Zug seiner Filmästhetik ausgemacht, dass es bei ihm in einem einzigen Film ganz verschiedenartige Bildauffassungen, Kadrierungen, Lichtsituationen gebe. Neuere Forschungen haben nachweisen können, dass Murnau das verschiedenartigste ikonographische Material der Kunstgeschichte, aber auch das seiner Zeit — etwa das Werk Franz Marcs — für seine Filmästhetik adaptierte und so der Formentwicklung des Films erschloss." "... Despite the detailed research of M. Bouvier and J.-L. Leutrat, the question of how Nosferatu came to be made is still something of a mystery. Virtually the only film produced by Prana-Film — a financial sinking ship whose owners were subsequently taken to court for copyright violations by Bram Stoker's widow despite having changed most of the characters' names — the project owed much to the enigmatic figure of Albin Grau, who signed for the decor and costumes but also seems to have been the driving force behind the production, both financially and artistically. Very little is known about Grau, though a recent article by Enno Patalas depicts him variously as a student of eastern philosophy, a freemason and master of the 'pansophic lodge of the light-seekers' in Berlin, a fan of Aleister Crowley, a friend of novelist-painter Alfred Kubin and the author of a pamphlet about the use of colour in decor and lighting in black-and-white films. More predictable collaborators were film-industry professionals screenwriter Henrik Galeen (who co-wrote The Golem) and director of photography Fritz Arno Wagner, one of the three top cameramen at Ufa. "Based illegally on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, F.W. Murnau’s film is undeniably the best and probably the most faithful of the myriad of films based on the novel. Naively, the film’s producers attempted to circumvent the author’s estate’s copyright by changing the names and central location of the film. ... |

|

|

|

1) DVD-Releases based on the definitive 1995 Bologna restauration The ultimate edition is yet to come. It should include the complete original German intertitles, the original score by Hans Erdmann which was restored in 1995, and the 1995 documentary by Luciano Berriatúa on Murnau's life and work, "El lenguaje de las sombras" (240 min) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kino on Video (released on 24 September 2002 in the USA, NTSC, Region 0) |

Kino on Video (Kino German Horror Classics) • Region 0 Follows the 1995 Bologna restauration. Two music tracks are supplied. "One by Donald Sosin, features synthesizer, pan pipes and a woman's voice, with cheesy cries and gasping for Ellen as she dreams of dark things. The other, by Gérard Hourbette and Thierry Zaboitzeff, is more atmospheric, with wind effects and occasional industral noises, and isn't terribly musical. ... A comparison of Harker/Hutter's meeting of the count and first meal is also provided, covering the original novel, Henrik Galeen's screenplay for Nosferatu, a clip from the film itself, and (unbilled on the package) Orson Welles' Mercury Theatre radio dramatization of Dracula from July 1938." (Digitally Obsessed)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

BiFi (British Film Institute, released on 21 January 2002 in the UK, PAL, Region 2) |

British Film Institute / Channel 4 Silents Edition (BFIVD520) • Region 2 (UK) The edition follows the 1995 Bologna restauration and consists of a Photoplay Production screened in 1997 by the TV station Channel Four in the UK. This explains for the new English intertitles of Framelines Graphics, but alas also for the fuzzy, low-resolution picture. The picture is windowboxed. The music is by the late James Bernard (1925-2001), composer of classic Hammer productions like The Quatermass Experiment (1955), Dracula (1958) and The Damned (1962), who in 1997 composed an orchestral score that was performed by the City of Prague Philharmonic for the Channel Four television presentation

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Film Sans Frontières (released in France in 1999, PAL, Region 0) |

Films Sans Frontieres 2, Collection Films du Siècle (EDV 1075) • Region 0 Runtime: 92:57 min Video: 1.33:1/4:3 FullScreen • Average Bitrate: 7.7 mb/s • PAL 720x576 Audio: Musical Score by Galeshka Moriavoff, MPEG-2.0 Stereo at 192 kb/s Intertitles: German with optional French or English subtitles Extras: • French b/w print which runs at 60:36 min at 24fps, French titlecards • Filmography of F.W.Murnau • Historical notes DVD Release Date: 23 November 1999 • Keep Case • Chapters: 5 • DVD Encoding: PAL Region 0 • SS-DL/DVD-9 The tinted edition is based on a used, dirty print of the 1995 Bologna version. The transfer doesn't render any of its qualities: grey pictures in a coloured sauce. (Enno Patalas) [Perhaps Patalas' judgement is too severe here, as Bram Blijleven's captures show a satisfying quality.]

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

2) DVD-Releases based on pre-1995 versions |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

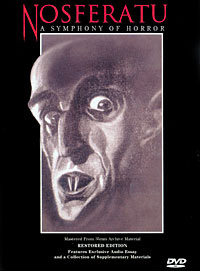

Image Entertainment (released on 2 January 2001 in the USA, NTSC, Region 0) |

Image Entertainment / Blackhawk Films Collection (ID0277DSDVD) • Region 0 (North America) Remastered Special Edition produced by David Shepard. "Mastered from 35mm Archive Material" (cover text) Runtime: 80:42 min Video: 1.30:1/4:3 FullScreen • Average Bitrate: 6.50 mb/s • NTSC 720x480 Audio: • Musical Score 5.0 Dolby Digital by the Silent Orchestra • Organ Musical Score by Timothy Howard Dolby Digital 2.0 Stereo • Audio Commentary Dolby Digital 2.0 Mono Intertitles: English Extras: • Audio Commentary by German silent film connoisseur Lokke Heiss • The NosferaTour (10:14 min) • The Phantom Carriage Ride (00:33 min) • Art Production Still Gallery • Production Notes DVD Release Date: 2 January 2001 • Snap Case • Chapters: 12 • DVD Encoding: NTSC Region 0 • SS-SL/DVD-5 Remastered release of the 1998 Image-Shepard-DVD (see below). Still follows the Second French Version (1926/27), plus a few new sequences, but again missing the sequences from the First French Version (1922) as well as from "The 12th Hour". New intertitles, the same as on the Eureka disc. Tinting colours are worse than on the 1998 DVD: there is no black, daylight is rendered in brown or gray etc. (Enno Patalas) DVD Beaver Comparison by Luiz Felipe do Vale Tavares and Alberto Ferraz D'Arce

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eureka Video (released on 22 January 2001 in the UK, PAL, Region 2) |

Disc 1 contains a monocoloured sepia version, disc 2 an "original" b/w version of the film, which was released from the very beginning in a five-colour tinting. The trailer claims that this version is based on "the last surviving print found in Germany", – a marketing lie, as Eureka's Ron Benson had to admit to Enno Patalas. The credits invoke the "National Archives Film Archives Koblenz, Town Museum Film Museum Munich and German Cinematic Foundation Berlin" (sic!), but in reality Eureka's version of the film is based on the 1981 Munich restauration (which at least contains some sequences not included on the Image Entertainment discs). The digital clean-up that was done for this edition at IML Digital Media Melbourne is so far the best digital processing of any German "classic" film on DVD. The graphics of the intertitles also follow basically the 1981 Munich restauration. The commentary is the same as on the Image DVDs, but spoken by an actor who tries in a involuntarily comical way to be emphatic. Roy Benson assured that the copyright holders Transit Film and Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau-Stiftung not only licensed, but also offered this obsolete 1981 version, without an alternative offer of the 1995 Bologna restauration. (Enno Patalas) DVD Beaver Comparison by Bram Blijleven

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Elite Entertainment (released on 22 Febuary 2000 in the USA, NTSC, Region 0) |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Image Entertainment (released on 21 July 1998 in the USA, NTSC, Region 0) |

Image Entertainment / Blackhawk Films Collection (ID4098DSDVD) • Region 0 (North America) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

3) Odds and ends: Some sub-standard public domain DVD editions |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

This is a strictly non-professional and non-commercial DVD review. Don't expect industry reference work! All ChiaroScuro captures are taken under MacOS X.2 using VideoLAN and Snapz ProX. For further methodological remarks see DVDBeaver (click on "Methodology"): "We are not a lab and are doing a good a job as our time and energy permits. Thank you for understanding." |

Last update: 8 Oct 2002