Земля | Zemlja

(Earth | Erde | La Terre)

by Oleksandr Dovženko

USSR 1930

(click poster to enlarge)

|

Director:

|

Oleksandr Dovženko | |

|

Production Companies:

|

VUFKO Studio Kiev | |

|

Screenplay:

|

Oleksandr Dovženko | |

|

Cinematographer:

|

Danylo Demuc’kyj (b/w, 1.37:1) | |

|

Editor:

|

Oleksandr Dovženko | |

|

Music Score:

|

V. Ovčinnikov (1971 Mosfilm print) | |

|

Art Director:

|

Vasilij Kričevskij | |

|

Assistant Director:

|

J. Solnceva-Dovženko, Lazar Bodik | |

|

Cast:

|

Semen Svačenko [Vasyl’], Stepan Škurat [Opanas, his father], Petr Masokha [Foma Belokon’], V. Krasenko [Peter], Nikolaj Nademskij [Semjon], P. Petrik [Young Communist Party cell leader], Julija Solnceva [Opanas’ daughter], Jelena Maksimova [Vasyl’s fiancee], I. Franko [Arkhip Belokon’], V. Mikhajlov [village priest], P. Umanec [Soviet farm chairman], E. Bondina [farm girl], Marija Matsjutsja [farm girl]

|

|

|

Runtime:

|

1740 m (64 min/24 fps; 76 min/20 fps; 95 min/16 fps) | |

|

Premiere:

|

8 April 1930 (USSR) |

|

"Dovzhenko is best known in the West for his epic silent films on the Soviet revolution - his "Ukrainian trilogy" of Zvenigora (28), Arsenal (29), and Earth

(Zemlya, 30). These films are firmly established in the silent cinema

canon, ensuring that Dovzhenko continues to be mentioned in the same

breath as his Soviet contemporaries Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Vertov

(their considerable stylistic differences notwithstanding). His

Ukrainian national identity and his peasant origins also figure in our

appreciation of him as a kind of rural bard, one whose work drew on

peasant lore and a pastoral tradition.

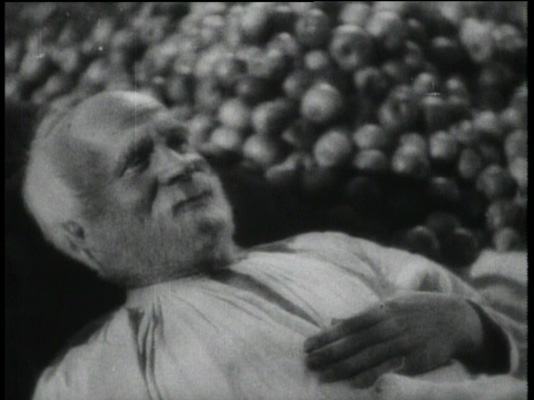

Dovzhenko was the most prominent of a lively avant-garde artistic cohort to emerge from Soviet Ukraine in the Twenties. Along with several writers and artists, he tried to formulate a Ukrainian national voice in the context of Soviet artistic culture. Since the breakup of the Soviet Union – and it's been over a decade now - the various Soviet republics have not only reformulated autonomous national identities but have worked to recover their cultural heritages from Soviet history. This mission was undertaken with particular urgency in the new Ukraine, offering at least one way to redress a record of subordination both to the old Russian Empire and to the Communist regime. ... Certainly new archival material made available in the past decade confirms the resentment Dovzhenko felt over the interference he endured from the ussr's Moscow-based Party apparat. But to portray him solely in national terms, as a kind of filmmaker-laureate of Ukraine, is to miss the most important quality of his work. That is precisely the tension between his indigenous Ukrainian sources and those modernist (and modernizing) influences that were activated by the Bolshevik Revolution. Throughout Dovzhenko's career two antagonistic pressures shaped his films: to celebrate the possibilities of Soviet-style revolution and the new Communist order, and to honor the tradition-based peasant heritage of Ukraine. The aesthetic richness of Dovzhenko's films results, in no small measure, from his effort to reconcile these antinomic goals. ... Dovzhenko's montage achieved particular rigor in Arsenal and Earth. As opposed to Eisenstein and Vertov's rapid, dynamic montage, Dovzhenko's editing has a more measured pace. But the cuts often involve substantial gaps in time and space. Viewers must find a logical connection from one shot to the next that isn't always provided by narrative continuity. ... the opening of Earth does little to move the narrative forward, but suggests a wealth of montage associations. The only story event in the entire first reel is the death of an elderly peasant. Dovzhenko edits the passage so as to take us repeatedly away from this incident to the details that seem to reside in some uncertain space around it: family members keeping vigil, children playing, the natural environment of trees, fruit, flowers, grain, and even clouds. The montage offers up subtle graphic associations between man and nature instead of narrative exposition. Such practices often taxed the patience of official Soviet critics, especially during the period of the Stalinist backlash against avant-garde art. Earth, in particular, earned the ire of Communist Party spokes-critics for being unduly abstract and for showing dangerous signs of "Ukrainian nationalism."That latter judgment coincided with the Kremlin's crackdown on "nationalist deviation" in the USSR's member republics. Dovzhenko felt this when his Kiev studio lost its autonomy in 1930 and was absorbed into the heavily bureaucratized Soviet film apparatus of the Stalin era. All the Soviet montage directors suffered under Stalinist constraints over the next decade, but Dovzhenko had the special burden of being labeled both a "formalist" (i.e., montage) and a "nationalist" (i.e., Ukrainian) filmmaker. Many of his associates in the Ukrainian intelligentsia, including the vaplite writers, disappeared in the purges, and Dovzhenko was able to survive by tempering his experimental style. With some difficulty, he adopted the sanctioned norms of Soviet socialist realism - linear narratives, continuity practices, optimistic plot formulas - and he even relocated from Kiev to Moscow later in his career to diminish the perception that he was a Ukrainian nationalist." — Vance Kepley, Jr.: Ukrainian Pastoral: How Alexander Dovzhenko brought the soviet avant-garde down to earth, Film Comment Magazine "Alexander Dovzhenko's ravishing and lyrical 1930 film about life on a collective farm in the Ukraine, the last and best of his silent features, shows his pantheism and poetry at their most exalting. The compositions are breathtaking, the evocations of death and social transformation powerful, the eroticism remarkably potent. Incontestably one of the greatest of all Soviet films." "Earth is the fourth and last silent film by the Ukrainian director Alexander Dovzhenko and is considered his masterpiece. Its story is very simple: the young peasants of a Ukrainian village want to set up collective farms; the kulaks (rich landowners) try to protect their land. Dovzhenko is concerned, not with plot, but with the lyrical expression of a universal theme: the life cycle of man (which Dovzhenko believes is bound inextricably to the land). The theme is developed through a constant juxtaposition and intertwining of images of life and death. In the opening sequence, shots of corn and wheat rippling in the wind, and fruit on the trees, suggest the harvest. Amidst these images of fertility, sunlight and happiness, an old man lies dying. He eats an apple, as does his young grandchild: life goes on, just as the fruit will continue to grow out of the earth. In the final sequence, Vasili, a young man whom a kulak has murdered, is buried by the peasants. His body is carried along the fields, past abundantly full apple trees. As he is placed in the soil, a peasant woman is shown in the pains of childbirth. Earth unfolds in cinematic space; there is a mad logic to its imagery, like the mad dance of its hero, Vasili, down the moonlit road to his death. Each startling image is precisely linked to the others much as the peasants it portrays are linked through their shared passions, miseries, and mysteries." "The astonishingly beautiful Earth

is unlike anything else in movies. Drafted to make a film on rural

collectivization, Dovzhenko produced a myth presenting the creation of

the kolkhoz as a natural phenomenon, part of a cosmic cycle of birth

and death. Murdered by a crazed kulak (or wealthy peasant), Earth's young hero is a martyr to the fertility of harvest. Released amid the campaign to liquidate the kulaks, Earth is ultimately a pagan myth made to celebrate a tragic social experiment." "La Pravda du 29 mars 1930 publie un article à l'emporte-pièce, signé par le dramaturge et cinéaste Pierre Bliakhine. Après avoir rendu hommage au talent de Dovjenko, l'originalité et la précision de ses modèles, le rythme et le contenu émotionnel du film, il l'accuse d'avoir montré des koulaks isolés, pitoyables, minimisant ainsi le danger qu'ils représentent. Bliakhine considère que le caractère de classe de ces personnages est absent du film, les motivations biologiques des héros se substituant aux motivations d'ordre socio-économique. En d'autres termes, aux yeux du parti, le film faisait preuve d'une haine insuffisante à l'égard des koulaks. ... Toutes ces critiques aboutiront à l'interdiction du film le 17 avril 1930. Les motifs politiques ayant inspiré cette mesure sont dissimulés sous des accusations de "biologisme", "panthéisme", "nationalisme", etc. : "par décision du Conseil Supérieur des Arts, le film est retiré du répertoire tant que les scènes montrant la femme nue et le mise en route du tracteur ne seront pas supprimées." ... |

|

|

||

|

Distribution:

|

Image Entertainment Region 0 (North America) |

|

|

Runtime:

|

69:47 min | |

|

Video:

|

1.30:1/4:3 FullScreen Average Bitrate: 5.72 mb/s NTSC 720x480 29.97 f/s |

|

|

Audio:

|

Orchestral Score Dolby Digital 1.0 Mono (composed and conducted for the 1971 Mosfilm print by V. Ovčinnikov | |

|

Subtitles:

|

Russian Intertitles with English Subtitles | |

|

Features:

|

• A reconstructed version of Sergej Èjsenštein's lost film Bežij Lug (USSR 1937, 31:18 min, 1.28:1/4:3 Windowboxed, 5.29 mb/s, Orchestral Score Dolby Digital 1.0 Mono)

|

|

| DVD Release Date: 22 January 2002 Keep Case Chapters: 8 DVD Encoding: NTSC Region 0 SS-SL/DVD-5 (2.92 GB/film, 4.17 GB/total) |

||

|

Comment:

|

The source print for the video transfer is supposed to originate from a 35mm print prepared in 1971 by Mosfil’m. But the print was prepared from materials that have been duplicated (since the negative was destroyed during the German invasion in WW II) until they almost look like a 16mm reduction print, with plugged-up shadow detail and exposure fluctuations. The transfer was taken from the old 1991 Kino video master and shows some evident video glitches, especially in the first five minutes of the picture. The film material itself is very worn, with scratches, tears and speckles throughout. The picture is cropped on all sides, sometimes cutting off the heads of the actors. The DVD encoding is clean and without problems, but one would wish for a visually more satisfying presentation of this movie.

As an extra, there is a reconstruction of Sergej Èjsenštein's lost 1937 film Bežij Lug, which consists entirely of a montage of still photographs. Film: **** out of ***** |

Menu

|

|

Frame 2

|

Frame 3

|

Frame 4

|

Frame 5

|

Frame 6

|

Frame 7

|

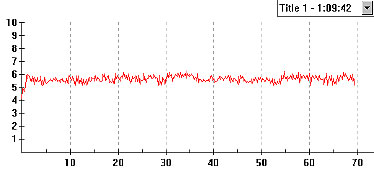

Average Bitrate :

5.72 mb/s

The Vertical axis represents the bits transferred per second. The Horizontal is the time in minutes

|

This is a strictly non-professional and non-commercial DVD review. Don't expect industry reference work! All ChiaroScuro captures are taken under MacOS X.2 using VideoLAN and Snapz ProX. For further methodological remarks see DVDBeaver (click on "Methodology"): "We are not a lab and are doing a good a job as our time and energy permits. Thank you for understanding." |