|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

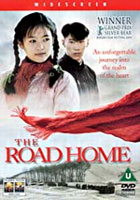

Wo de fu qin mu qin

(Heimweg | The Road Home)

|

|

|

| |

|

China 1999 - 89 Minuten -

Regie: Zhang Yimou

Produzent: Yu Zhao

Executive Producer: Zhang Weiping

Produktion: Beijing New Picture Distribution Company / Columbia Pictures Film Production Asia / Guangxi Film Studio

Drehbuch: Bao Shi, nach seinem Roman Remembrance

Kamera: Hou Yong (Color, 2.35:1 Panavision 35 mm)

Schnitt: Zhai Ru

Musik: Bao San

Ton: Wu Lala (Dolby SR)

Bauten: Cao Jiuping

Kostüme: Tong Huamiao

Darsteller: Ziyi Zhang (Zhao Di, Young), Honglei Sun (Luo Yusheng), Hao Zheng (Luo Changyu), Yuelin Zhao (Zhao Di, Old), Bin Li (Grandmother), Guifa Chang (Mayor, Old), Wencheng Sung (Mayor)

Premiere: 15 Februar 2000 (Berliner Film Festival)

Auszeichnungen: Berliner Internationales Film Festival 2000: Preis der Ökumenischen Jury; Silberner Bär • Sundance Film Festival 2001 Audience Award World Cinema

|

|

|

International Movie Database International Movie Database |

All-Movie Guide All-Movie Guide |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

Zhang Yimou's gorgeously photographed, richly emotional ode to family is among the most memorable films of his varied career, managing to tell its conventional tale with unconventional wisdom and no shortage of true empathy and heart. Broken up beautifully in stark black-and-white for the modern scenes and a lush colorization in flashback, the movie isn't terribly surprising in its execution, but Yimou's expert realization of the themes the film explores more than compensates. Zhang Ziyi, who made such an indelible impression in 2000's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is even more luminous here, in a performance based more on instinct than words, and her beauty is even more captivating, not unlike the starlets of old Hollywood. The film seems rooted in old-fashioned romantic splendor (also not unlike old Hollywood), skillfully blending Eastern idealism and Western ambition into one moving, deeply admirable achievement. Zhang Yimou's gorgeously photographed, richly emotional ode to family is among the most memorable films of his varied career, managing to tell its conventional tale with unconventional wisdom and no shortage of true empathy and heart. Broken up beautifully in stark black-and-white for the modern scenes and a lush colorization in flashback, the movie isn't terribly surprising in its execution, but Yimou's expert realization of the themes the film explores more than compensates. Zhang Ziyi, who made such an indelible impression in 2000's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is even more luminous here, in a performance based more on instinct than words, and her beauty is even more captivating, not unlike the starlets of old Hollywood. The film seems rooted in old-fashioned romantic splendor (also not unlike old Hollywood), skillfully blending Eastern idealism and Western ambition into one moving, deeply admirable achievement.

Very much a companion piece to ‘Not One Less’, Zhang Yimou’s new film is another sincere, didactic tearjerker from rural China. Education and civilisation are central themes in both, and they even share a sequence in which the obstinate young heroine runs like the clappers in pursuit of a teacher driving away from the village to the city. There are differences, though. While it begins and ends in the present day, the heart of ‘The Road Home’ unfolds in flashback, as Luo Changyu (Zheng Hao) remembers the oft-told story of his parents’ courtship back in the late 1950s: how Zhao Di (Zhang Ziyi) scandalised the village by falling in love with the fresh-faced young schoolteacher (Sun Honglei), just as he was recalled to the city to account for unspecified political crimes.

While the present-day scenes are shot in chilly blue monochrome (Luo has returned home for his father’s funeral), the love-story drips sensuous, saturated colour — Zhao Di’s bright-red coat against the golden haze of the cornfields becomes a symbol of her devotion. Forsaking the handheld, documentary-style of ‘Not One Less’, Zhang favours classical, balanced compositions and crisp but straightforward cuts: this is old-fashioned story-telling, with lots of voice-over narration and an emotive score. Presumably we’re meant to read this as the son’s idealised conception of his mother’s nostalgic memories. Even so, the film might be criticised for sentimentalising rural poverty: Zhang dresses it up in visual luxuriance worthy of Visconti’s aristocrats. The opening shot is a knowing tip-of-the-cap to Abbas Kiarostami. Five minutes later, it’s impossible not to notice the posters for ‘Titanic’ looming incongruously on a peasant’s wall. Sadly, affecting the simplicity of the former, Zhang ultimately approximates the bathos of the latter.

Auszüge aus einem Interview mit Zhang Yimou

Die chinesische Gesellschaft wandelt sich derartig rasch, dass die meisten Leute sich nicht mehr zurechtfinden. Das chinesische Kino spiegelt diese Entwicklung wieder. Heutzutage wird alles von der Marktwirtschaft bestimmt und unser Kulturleben entwickelt sich in die falsche Richtung. Die meisten Filme, die jetzt im Kino erscheinen, sind wirklich vulgär. Regisseure, die sich früher für derartige Filme geschämt hätten, setzen heute stolz ihren Namen davor. Das ist eine bedauerliche Situation, und ich frage mich, ob die Leute solche Filme wirklich mögen. Ich habe meine letzten beiden Filme Keiner weniger — Not One Less und Heimweg — The Road Home als Reaktion auf die gegenwärtigen Tendenzen im chinesischen Kino gemacht, gegen die Logik des Marktes. Ich wollte, dass sie einfach, direkt und realitätsverbunden sind. Ich glaube, dass sie vom Publikum angenommen werden, denn sie sprechen den Zuschauer mit echten Gefühlen und Emotionen an. Die chinesische Gesellschaft wandelt sich derartig rasch, dass die meisten Leute sich nicht mehr zurechtfinden. Das chinesische Kino spiegelt diese Entwicklung wieder. Heutzutage wird alles von der Marktwirtschaft bestimmt und unser Kulturleben entwickelt sich in die falsche Richtung. Die meisten Filme, die jetzt im Kino erscheinen, sind wirklich vulgär. Regisseure, die sich früher für derartige Filme geschämt hätten, setzen heute stolz ihren Namen davor. Das ist eine bedauerliche Situation, und ich frage mich, ob die Leute solche Filme wirklich mögen. Ich habe meine letzten beiden Filme Keiner weniger — Not One Less und Heimweg — The Road Home als Reaktion auf die gegenwärtigen Tendenzen im chinesischen Kino gemacht, gegen die Logik des Marktes. Ich wollte, dass sie einfach, direkt und realitätsverbunden sind. Ich glaube, dass sie vom Publikum angenommen werden, denn sie sprechen den Zuschauer mit echten Gefühlen und Emotionen an.

Die Budgets für die beiden Filme waren weit geringer als die, die ich für Produktionenen wie Shanghai Serenade zur Verfügung hatte. Ich wollte die Gedanken und Träume einfacher Leute im ausgehenden 20. Jahrhundert darstellen, ein Jahrhundert, in dem sich China in Folge vieler Umwälzungen radikal verändert hat. Der Druck des Marktes ist immens. Wir wollen uns selber treu bleiben, aber wie stellen wir das an? In den 80er Jahren haben Filme ihr Publikum wie selbstverständlich gefunden, jetzt ist es viel schwerer. Aber ich bin stolz, dass ich diese beiden Filme gemacht habe. Es ist unsere Pflicht, die besten Traditionen des chinesischen Kinos zu bewahren. Schauen Sie sich den italienischen Neorealismus oder die französische Nouvelle Vague an: Die haben etwas Bleibendes geschaffen, das ist eine schöne Tradition. Das chinesische Kino sollte sich nicht so sehr von Hollywood beeinflussen lassen.

Mir gefallen die Filme von Abbas Kiarostami sehr, und ich unterhalte mich mit meinen Freunden oft über das iranische Kino. Ich sage ihnen: "Schaut mal, wir glauben, wir hätten es schwer hier in China, aber der Druck des orthodoxen Islam im Iran ist weit schlimmer als alles, was wir hier aushalten müssen. Doch trotz des Drucks gelingt es iranischen Regisseuren, grossartige Filme zu machen!" Worauf es wirklich ankommt, sind nicht unsere Lebensumstände oder der historische Moment, sondern die innigsten Vorstellungen des Regisseurs, was er oder sie ausdrücken will, wie es ausgedrückt wird, die zugrunde liegenden Prinzipien. In dieser Hinsicht kann man vom iranischen Kino lernen.

HEIMWEG spielt in der Gegenwart und unterscheidet sich stark von Keiner weniger – Not One Less. Der Film steht einer anderen chinesischen Tradition nahe, der poetischen Erzählung. Er orientiert sich an einer bestimmten Auffassung von Schönheit, die sorgfältig in Cinemascope Bildern eingefangen wird.

Die Hälfte der Darsteller im Film sind Laien. Ich hatte grosse Schwierigkeiten, sie zu finden, wie schon bei den Laiendarstellern in Keiner weniger – Not One Less. Und die professionellen Schauspieler im Film sind sehr jung, sie haben nicht viel Berufserfahrung, das gilt insbesondere für die beiden Hauptdarsteller in der langen Rückblende, beide sind 20 Jahre alt. Die Handlung ist sehr simpel, sie entwickelt sich anhand der Figur, die sie erzählt. Das ist ein Mann, der in der Stadt arbeitet, weit weg vom Dorf, in dem er geboren wurde. Als sein Vater stirbt, kehrt er zum Begräbnis nach Hause zurück. Er verbringt drei Tage mit der Mutter und denkt an die Zeit zurück, als seine Eltern sich kennenlernten und ineinander verliebten.

Es gibt eine autobiographische Komponente in dieser Handlung, obwohl ich im Film nicht meine eigene Geschichte erzähle. Mein eigener Vater starb 1997, als ich an "Turandot" für das Opernhaus in Florenz arbeitete. Ich war nicht bei ihm, als er starb. Ich kehrte zu seiner Beisetzung nach Xian zurück.

Dies ist ein Film über Liebe, über Familie, über die Liebe zwischen Familienmitgliedern. Ein einfaches Mädchen vom Dorf verliebt sich in einen Grundschullehrer, und ihre Liebesgeschichte entwickelt sich vor dem historischen Hintergrund einer besonders schwierigen Phase in der Geschichte des modernen Chinas. Bisher haben sich Künstler mit dieser Zeitperiode auf eine sehr ernste und analytische Art beschäftigt, ich habe es dagegen vorgezogen, diese reine und einfache Liebesgeschichte auf eine poesievollere und romantische Art und Weise zu erzählen. Es war gerade diese Art wahrer Liebe, die es uns ermöglichte, derart schwere Zeiten in unserem Leben zu überstehen.

Zum anderen geht es, sowohl in der Rückblende wie auch in den zur heutigen Zeit spielenden Teilen des Films, um den Wert der Bildung. Der Film zeigt die Einstellung der Landbevölkerung zur Bildung — sie ist im wesentlichen von Respekt und Ehrfurcht geprägt. Es wird deutlich gemacht, welche Einstellung das chinesische Volk zu zwei bestimmten Zeitpunkten in unserer modernen Geschichte zum "Lernen" gehabt hat. Der erste Zeitpunkt liegt einige Jahrzehnte zurück. Aus rein politischen Erwägungen wurde Bildung brutal herabgewürdigt. Intellektuelle wurden physisch misshandelt und verschwanden in der Versenkung. Der zweite Zeitpunkt ist die Gegenwart. Heute ist jedem klar, das Wissen Macht bedeutet, und trotzdem ist Lernen wieder unpopulär. Stattdessen denken viele von uns ultra-materialistisch, denken nur noch an Geld.

Es ging mir bei diesem Film darum, diese grundsätzlichen Themen im Kontext mit der chinesischen Gesellschaft und Geschichte erneut zu beleuchten.

In considering a response to The Road Home, I am thinking how contrived, unnatural and, why not, futile, recent western cinematic productions seem. — Have you seen Bats? — And then, this meeting between Australian scriptwriters and funding bodies, which took place last year, comes to mind. Every story presented by the scriptwriters was convoluted with too many undercover agents and some predictable hairdressers as well. Which makes me wonder: having abandoned simplicity and plain story-telling are we being rather kind in our critical response to the "exotic" films from say China, Iran or Madagascar?

In The Road Home, Zhang Yimou returns to the plateau of his last film, the village school, collaborating with the cinematographer and the music composer from the said Not One Less (1999). With this text though, his dramatics are more affecting and effective. The centre of the story this time is the life and love of the village school teacher and his wife of forty years. Told in flashback by their son, who has returned to the village to arrange the burial of his father, the film is startling in its choice of opening style and scenes. In grainy black and white, we are looking at a jeep driving through snowy mountain roads; the son’s homecoming, or maybe an aftershave commercial. — Indeed, throughout the film, the present remains dark, whilst the past/flashback is told in rich and warm colour. — When the son meets the mourning mother, we learn of her desire to bring the coffin from the city back to the village on foot, carried by local men, as is the custom. As importantly though, we discover the story of the parents’ courtship, which is known to everybody in the village. In The Road Home, Zhang Yimou returns to the plateau of his last film, the village school, collaborating with the cinematographer and the music composer from the said Not One Less (1999). With this text though, his dramatics are more affecting and effective. The centre of the story this time is the life and love of the village school teacher and his wife of forty years. Told in flashback by their son, who has returned to the village to arrange the burial of his father, the film is startling in its choice of opening style and scenes. In grainy black and white, we are looking at a jeep driving through snowy mountain roads; the son’s homecoming, or maybe an aftershave commercial. — Indeed, throughout the film, the present remains dark, whilst the past/flashback is told in rich and warm colour. — When the son meets the mourning mother, we learn of her desire to bring the coffin from the city back to the village on foot, carried by local men, as is the custom. As importantly though, we discover the story of the parents’ courtship, which is known to everybody in the village.

The flashback story begins with the new teacher’s arrival in the village and it is propelled when the village beauty tries to attract his attention. By the time the teacher responds, he is taken away ‘for questioning’ in the city. Before leaving though, he steals the time to leave a little gift, a hair pin to the girl, and promises to return. While away for a long time, the girl takes care of the school and when she hears of the teacher’s return, she sets off through snow and windstorms to welcome him. Collapsing in the snow, she is brought home to find the teacher was by her bedside for hours, but because he left the city without permission he is punished, for this is the time of the Cultural Revolution. The teacher will be allowed back to the village in two years’ time, and again the girl is waiting for him along the road home when he returns. This is the same road the mother wants the funeral procession to follow when they return the coffin for burial. — I prefer referring to the characters as father/teacher and girl/mother because in my western ears their written names do not correspond to their pronounced sounds.

I do not want to point to the smallness (read delicacy) of gestures, or the innocence of dramatic construction. Look at the two posters of the movie Titanic, strategically positioned in the old parents’ home, maybe as an attempt at sarcasm by Zhang. As for the cinematography, even when in full Cinemascope, I did think it felt somewhat agricultural. No, this is not a film of atmospherics. What we find in The Road Home is perfectly crafted story-telling of irresistible charm. Zhang sees this work a reaction to vulgarity and a return to a chinese — but not only — tradition: the poetic narrative. The magic for this commentator is distilled in the mother’s statement: "I cannot read but for forty years I would walk to the school and I would stand outside to hear his voice reading". Cinematically it may be innocent but dramatically it is undeniably affecting. Although I did see the film in a media screening with seasoned viewers, I was not the only one with moist eyes at the end. See if you can resist!

At a higher level, it offers a case for what environment may be fertile for great art. Again reading from Zhang’s manifesto: "Look, we think we have it hard here in China, but the pressures of Islamic Orthodoxy in Iran are far worse than anything we have to contend with here. But despite the pressures, Iranian directors succed in making great films." There lies, I believe, the humility of a great creator.

Chinas Frauen — zurück in die Zukunft

Zhang Yimous «The Road Home — Heimweg» ist eine Liebeserklärung an die Tradition

Die Strasse ist das zentrale Motiv der vor zwei Jahren unmittelbar hintereinander entstandenen beiden Filme von Zhang Yimou, und in beiden wird sie zum «Heimweg». In «Keiner weniger» kehrt im Finale eine junge Lehrerin mit ihrem verloren gegangenen Schüler ins Dorf zurück — ein Neuanfang. In «Heimweg» soll der in der Kreisstadt verstorbene Lehrer nach alter Sitte in sein Heimatdorf übergeführt werden — ein letzter Gang, ein Begräbnis. Beide Filme spielen in der Gegenwart, aber «Heimweg» hält noch einmal Rückschau auf die Elterngeneration, die, wie Zhang Yimou selbst, Maos China und die Kulturrevolution erlebt hat, und spielt indirekt auf diesen einschneidendsten Abschnitt in der Geschichte der Volksrepublik an, in dem viele Familien zerrissen, der Generationenvertrag aufgehoben und das chinesische Kulturerbe zerstört wurden.

Zhang Yimou musste dafür auf der letzten Berlinale herbe Kritik für einen «reaktionären Propagandafilm» oder für eine «stalinistisch-maoistisch» inspirierte Ästhetik einstecken. Wenn man genauer hinschaut, kann man in «Heimweg» eine zutiefst humane poetische Erzählung entdecken, die nicht ideologisch Stellung bezieht, sondern sich um einen ganzheitlichen Blick auf die chinesische Gesellschaft bemüht. In der schwarzweiss gehaltenen Rahmenhandlung reist der Geschäftsmann Luo Yusheng zur Beerdigung seines überraschend verstorbenen Vaters ins heimatliche Bergdorf. Er unternimmt die nötigen Schritte, um den Wunsch seiner Mutter zu erfüllen, dass der Sarg den weiten Weg vom Spital zurück ins Dorf von den Männern des Dorfes getragen werden soll. Ausserdem hat sie schon damit begonnen, das traditionelle Totentuch zu weben. Der einzige Sohn beugt sich notgedrungen dem Willen der störrischen alten Frau. Zhang Yimou musste dafür auf der letzten Berlinale herbe Kritik für einen «reaktionären Propagandafilm» oder für eine «stalinistisch-maoistisch» inspirierte Ästhetik einstecken. Wenn man genauer hinschaut, kann man in «Heimweg» eine zutiefst humane poetische Erzählung entdecken, die nicht ideologisch Stellung bezieht, sondern sich um einen ganzheitlichen Blick auf die chinesische Gesellschaft bemüht. In der schwarzweiss gehaltenen Rahmenhandlung reist der Geschäftsmann Luo Yusheng zur Beerdigung seines überraschend verstorbenen Vaters ins heimatliche Bergdorf. Er unternimmt die nötigen Schritte, um den Wunsch seiner Mutter zu erfüllen, dass der Sarg den weiten Weg vom Spital zurück ins Dorf von den Männern des Dorfes getragen werden soll. Ausserdem hat sie schon damit begonnen, das traditionelle Totentuch zu weben. Der einzige Sohn beugt sich notgedrungen dem Willen der störrischen alten Frau.

Mit einem Blick auf das Hochzeitsbild wird eine lange Rückblende ausgelöst, die den Film in ein überwältigendes Farbenmeer taucht, um eine Liebesgeschichte zu erzählen, die weit übers Dorf hinaus bekannt geworden ist. Wie im Märchen kommt eines Tages ein junger Lehrer mit dem Pferdewagen ins Dorf gefahren und wird von Anfang an mit Blicken verfolgt von der jungen Zhao Di (Zhang Ziyi) , die ihre schönste, leuchtend rote Jacke anzieht, ihm die feinsten Speisen kocht und sich ihm eines Tages kurz entschlossen in den Weg stellt, als er seine Schüler nach Hause begleitet. Sie setzt schliesslich ihre Liebe durch - die Erste im Dorf, die sich aus Liebe ihren Mann selbst erwählt.

Der Film blättert diese Geschichte wie ein Erinnerungsalbum auf, das in Zhang'scher Erzähltradition die Selbständigkeit einer jungen und starken Frau herauskehrt, wie in «Das rote Kornfeld» (1988) oder «Rote Laterne» (1991). Als ihr Liebster kurze Zeit darauf als Rechtsabweichler verdächtigt und abgeholt wird, bricht eine Zeit des Wartens, des Verzichts und des Schweigens an, die von Di beinah mit dem Tod bezahlt wird. Erst zum Schluss wird das Vergehen des jungen Lehrers genannt, der kein offizielles Lehrbuch benutzt hatte, sondern mit einem selbst verfassten Brevier dazu aufforderte, den Blick sowohl in die Gegenwart als auch die Vergangenheit zu lenken.

Der wiederum in die Rahmenhandlung eingebettete Beerdigungszug gerät mit über hundert Teilnehmern zu einem Triumphzug. Leute aus den Nachbardörfern, ehemalige Schüler reihen sich ein, um ihrem Lehrer das letzte Geleit zu geben. Alle stiften ihren Trägerlohn für eine neue Schule, ein letzter Wunsch des Verstorbenen. «Heimweg» erzählt eine ganz einfache Fabel, seine Sprachgewalt liegt in den betörenden, künstlich überhöhten, Gefühle mobilisierenden Farben der Rückblende, in seinen traumhaften Überblendungen, die mit ganz einfachen Mitteln vergehende Zeit veranschaulichen und von einer traditionellen Musik untermalt werden. Die aus der Perspektive der jungen Frau erzählte Geschichte benutzt die Ikonographie der populären Bildgeschichten, die sprechende maoistische Bildersprache, die hier allerdings auch für die Sprache einer Leseunkundigen steht: Es ist die Sprache ihrer Erinnerung.

Das Filmplakat von James Camerons «Titanic» im Zimmer der Witwe verweist hingegen auf das gegenwärtige chinesische Kino, das dem Hollywoodfieber erlegen ist. Während Zhang mit den Stilmitteln des Melodramas seine chinesische Geschichte erzählt, die von einer alles überwindenden Liebe durchglüht und keinesfalls vom pädagogischen Zeigefinger eines maoistischen Lehrstücks über den Segen der Dorfschule bestimmt wird. Letztlich setzen alle Filme Zhangs, die sich mit der Stadt-Land-Problematik auseinandersetzen — der erste dieser Art war «Die Geschichte der Qui Ju» (1992) — das bäuerliche Leben und seine Traditionen als Widerstand gegen eine anonyme und bürokratische Stadtgesellschaft ein.

Die übergreifende Metapher dieser beiden neuen Filme muss heute so gelesen werden, dass die Verbindung zwischen den beiden Kulturen, der bäuerlich-archaischen und der eines modernen China, quasi abgebrochen ist. Beide drückenunterschwellig Besorgnis über eine «neue» Kulturrevolution aus, die ebenso radikal wie die Bilderstürmerei der Roten Garden das in der kurzen liberalen Öffnungsphase der frühen achtziger Jahre mühsam geflickte Netz wieder zu zerreissen droht, das so etwas wie kontinuierliche Geschichtserfahrung und Geschichtsbewusstsein und damit ein neues Lernen entwerfen sollte. Mit welcher Behutsamkeit die Vergangenheit wiederbelebt und gepflegt werden sollte, führt Zhang paradigmatisch vor, wenn er eine zerbrochene Schale — quasi eine Reliquie der Erinnerung — vom umherziehenden Porzellanflicker mit einer Klammer reparieren lässt. Eine kleine kostspielige Arbeit, die Zhang in allen Arbeitsgängen vorführt, als solle dem alten, heute überflüssigen Handwerk ein Denkmal gesetzt werden. — «Heimweg» wurde von Columbia Pictures Film Production Asia finanziert, die sich auch die weltweiten Verleihrechte für «Keiner weniger» und Ang Lees «Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon» sicherte. Die Fachzeitschrift «Screen International» erlaubte sich für diese gelungene amerikanisch-chinesische Zusammenarbeit die frohlockende Überschrift: «Cultural evolution». Man kann nur hoffen, dass diese neuen Filme irgendwann auch ins chinesische Kino finden, das, wie Zhang Yimou sich beklagt, derzeit von «vulgären, kommerziellen» Filmen überschwemmt wird. Zhangs «Heimweg-Thematik» dürfte daher auch als Hinweis darauf zu lesen sein, dass er seinen Weg noch lange nicht zu Ende gegangen ist, dass er, als populärster chinesischer Filmemacher und Abgeordneter der Nationalversammlung, seinen Weg in der Heimat aber nur auf diese Weise gehen kann und muss.

Two Lives in China, With Mao Lurking

Zhang Yimou's tenderhearted film "The Road Home" is a cinematic ballad of such seamless construction and exquisite tonal balance it transcends most of the pitfalls of movies that aspire to a classic, lyric simplicity. The one grating element is a redundantly schmaltzy soundtrack by San Bao that shamelessly imitates James Horner's quieter theme music for "Titanic" and nudges "The Road Home" toward an emotional grandiosity. But that pushiness, thankfully, does not extend to the rest of the movie.

Mr. Zhang, whose credits include "Red Sorghum," "Raise the Red Lantern," and "The Story of Qiu Ju," was a cinematographer before becoming a director, and his mastery of color and mood and his attunement to nature lend this elemental love story a penetrating hum of universality. Much of the film is set during the winter in a pristine, hilly region of northern China that is connected to the outside world by a single unpaved road. There is no electricity in the town, and water is pumped from two wells. Mr. Zhang, whose credits include "Red Sorghum," "Raise the Red Lantern," and "The Story of Qiu Ju," was a cinematographer before becoming a director, and his mastery of color and mood and his attunement to nature lend this elemental love story a penetrating hum of universality. Much of the film is set during the winter in a pristine, hilly region of northern China that is connected to the outside world by a single unpaved road. There is no electricity in the town, and water is pumped from two wells.

Saturated in a bluish winter snowlight and filmed with an extraordinary sensitivity to the changing seasons, the weather and the time of day, these scenes are so atmospheric they beckon you into a childlike state of wondrous apprehension. Before the engulfing realities of wind, snow, sky and cold and the sound of crunching boots, nagging everyday thoughts recede into the background.

A major influence on "The Road Home," Mr. Zhang has said, is contemporary Iranian cinema, especially the movies of Abbas Kierostami, which convey a similarly ecstatic awareness of the natural world. But "The Road Home" isn't as austere as Mr. Kierostami's work. Its panoramic shots of the village nestled in the snowy hills in the dead of winter and of grain fields blazing gold in the late summer heat are unabashedly gorgeous and fraught with a nostalgic poignancy that one doesn't feel in Iranian films in which the atmosphere tends to be more mystically spiritual.

The film's overwhelming sense of a purifying return to nature helps compensate for its central characters — two humble but luminous young people living in a remote Chinese village during the Cultural Revolution — not being sharply etched.

The story is narrated by Luo Yusheng (Sun Honglei), a young engineer who, upon the sudden death of his father, returns from the city to the village of Sanheutun, where he was born. When the funeral arrangements are discussed, his wizened mother, crushed with grief, insists that traditional custom be observed and the body be carried on foot by local residents the considerable distance from the hospital back to the village.

As Yusheng contemplates his father's death, he begins to reminisce about his parents' marriage, and the movie, whose opening scenes are filmed in a grim bluish gray, bursts into brilliant color. We meet Luo's mother Zhao Di (Zhang Ziyi) when she was a radiant 18-year-old who falls in love at first sight with Luo Changyu (Zheng Hao) the handsome 20-year-old schoolmaster who arrives from the city.

For the first third of the movie Di, the prettiest girl in the village who has resisted entering into an arranged marriage while tending her blind but canny mother (Li Bin), throws herself at the visitor, who soon notices and shyly reciprocates her interest.

When the villagers build the schoolhouse in which Changyu will spend most of the rest of his life teaching primary school, she lovingly weaves the traditional red cloth to be wound around its rafters. Visiting the school daily, she stands outside, listening enchantedly to the sound of his mellifluous voice as he drills the students in quasimilitary calls and responses.

Ms. Zhang's intensely concentrated performance conveys a current of stubborn, obsessive passion lurking behind Di's girlish wide-eyed innocence. This is a woman who, on recognizing her destiny, will let nothing stand in the way of her seizing it. When Changyu gives her a simple ornamental hairpin, it becomes a precious icon.

The chaste courtship is painfully interrupted when Changyu is called back to the city to face interrogation for unspecified political reasons, and Di, who has pinned all her hopes on his return, nearly dies of a fever caught waiting by the road for him to return on the day he promised.

"The Road Home" isn't about politics but about how the echoes of ideological wars waged in distant capitals affect ordinary people who have only the most tenuous connections with those struggles. In villages like Sanheutun, life goes on as usual, and change, when it comes, arrives gradually. Not once in the film is the name Mao Zedong mentioned or his image shown. The revolution that turned most of China upside down is merely a dim flicker of lightning beyond the wintry horizon.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

DVD

|

The Road Home

Columbia TriStar Home Video

|

| Länge: |

85:45 min (= 89 min PAL) |

| Video: |

- 2.32:1/16:9 Anamorphic WideScreen

|

| Bitrate: |

|

| Audio: |

- Mandarin Dolby Digital 5.1 Surround

|

| Untertitel: |

- English

- Polski

- Ceské

- Magyar

- Hindi

- Türkçe

- Arabic

- Dansk

- Svenska

- Suomi

- Nederlands

- Norsk

- Íslenska

- Português

- Hellenikê

- Hebrew

- Bulgarski

|

| Features: |

|

| DVD-VÖ: |

16 April 2001 |

|

Keep Case

Chapter stops: 28

DVD Encoding: PAL Region 2 (UK)

SS-SL/DVD-5 |

Full credit to Columbia for providing a flawless 2:35:1 anamorphic video transfer of the film. The bookend, present day scenes are presented in black and white while the main story is colour. As this is a Region 2 PAL release, it is hard to imagine this film looking any better. The sheer opulence and crystal clarity of colour and light on display and the stunning cinematography are given the treatment they deserve here. Full credit to Columbia for providing a flawless 2:35:1 anamorphic video transfer of the film. The bookend, present day scenes are presented in black and white while the main story is colour. As this is a Region 2 PAL release, it is hard to imagine this film looking any better. The sheer opulence and crystal clarity of colour and light on display and the stunning cinematography are given the treatment they deserve here.

The soundtrack is Dolby Digital 5.1 and the sound is well used on all the speakers. It is particularly effective as the film boasts a beautiful original score by San Bao.

Extras — there are none, but I don’t think the DVD suffers from the lack of features and I wouldn’t mark down the overall score for the film on this shortfall. I am not a big fan of extras and especially here with such a simple and beautiful film — presented perfectly in anamorphic widescreen with DD 5.1 sound — everything you need is presented in the feature. I can’t see anything more that additional features could add to the enjoyment of the film.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg) |

|

|

![[filmGremium Home]](../../image/logokl.jpg)