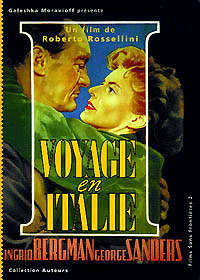

Some films have to be seen to be believed: the secret of this most beautiful and magical of films is ‘nothing happens’. From the slight tale of a bored English couple holidaying in Italy, Rossellini builds a magnificently passionate story of cruelty and cynicism swirling into a renewal of love: life is so short, we must make the most of it… Rarely has screen chemistry worked so indefinably well; Sanders’ suave, caddish business-man superbly complements Bergman’s Garbo-like presence and the sensous locations in which they feel so ill at ease. And though critics may have always praised it as ‘one of the most beautiful films ever made’, its genuinely romantic tenderness (it ends in ‘I love you’) mark it as never so unfashionable, never so moving.

The third, and, many feel, the best of the five very personal features Roberto Rossellini made with Ingrid Bergman, Voyage to Italy is the key link between neorealism and the subjective cinema of the early sixties. Bergman and George Sanders portray an English couple on a visit to Italy to sell a family mansion. The film is "about" the disintegration and regeneration of their marriage; on a deeper level, it is about the spiritual needs of modern men and women in a world in which men, due to their roles in capitalist society, are seen by Rossellini as more alienated (and psychologically handicapped) than women. If this theme anticipates Antonioni, so does the treatment which rejects "plot" for a direct, intuitive cinema that exploits the tensions between actor and character, characters and landscape, documentary and symbolic shots, in a way that is, for 1953, nothing short of revolutionary.

VOYAGE TO ITALY was critically savaged when it was first released in the US in an English version called STRANGERS, running nearly 20-minutes shorter than the original. It was attacked as being "dull," "plodding," "slow," "hackneyed," "meandering," "poorly photographed," "poorly written," and "incompetently directed." At the same time, the French "new wave" critics called it a masterpiece: Jacques Rivette wrote that on its appearance, "all other films suddenly aged 10 years," and Jean-Luc Godard rhapsodically described it as being among "the most beautiful of films." Beyond the obvious differences of the original with the shortened version, this brings up the interesting question of what exactly "beauty" means in the context of the cinema. Is it just the presentation of pretty pictures and professional acting, artfully composed and photographed, proficiently assembled and conforming to a proscribed set of narrative conventions designed to elicit the expected responses of laughs and tears? Or is there beauty in the truthful, unmelodramatic observation of people, in an attempt to examine the human soul and such existential intangibles as life, death, history and time? If it is the latter, then VOYAGE TO ITALY really is among the most beautiful of films.

The Joyces' voyage is a spiritual journey in which the beauty, and the horror, of the Italian landscape makes them reflect on the emptiness of their lives (their need to always be with other people; Katherine's jealousy upon seeing so many pregnant women), as well as their mortality, (the increasingly disturbing trips to the ruins, culminating with the shocking Pompeii discovery). The scenes in the museums, ruins, and volcanoes have a mystical, timeless quality to them which truly are beautiful, with the camera eerily circling around the statues (a camera movement Godard copied verbatim in 1963's CONTEMPT, along with the scene of the characters sunning themselves on the roof of the Italian villa). The film is slow and plodding, but the lack of a traditional plot is exactly the point, as reflected in Alexander's constant complaints of boredom and his comment that "this country poisons you with laziness." Bergman (who was Rossellini's wife at the time) is stripped of her usual glamour, while Rossellini cuts through Sanders's cultivated facade of sarcastic disdain, presenting him as a real human being for perhaps the only time on film. By the accumulation of mundane details of everyday life--eating, driving, sleeping, quarreling--Rossellini creates a kind of scientific verisimilitude and realism that's detached, but never impassive, and the reconciliation climax is moving precisely because of its casual naturalism and lack of hyperbole. VOYAGE TO ITALY is a documentary love story about cruelty, kindness, and the brevity of life, inspiring one to examine one's own conscience and realize just how precious life really is.

Michael Scheinfeld, www.tvguide.com

The history of the Italian critical reception of Viaggio in Italia reflects a singular chronicle of incomprehension, whereas in France the film was greeted with exaggerated, sometimes delirious praise. Attacks upon the film in Italy surpassed previous levels of invective. For example, one article advised Rossellini to find another means of employment: "The only possibility still remaining to Rossellini in considering himself a great director is that of definitively retiring from the screen and of removing from circulation his last four or five films. To change one’s profession in certain circumstances is, without a doubt, the wisest thing one can do”.

Another venomous review found fault with every detail of the film: "Viaggio in Italia does nothing but confirm the absolute, progressive, and irremediable decadence of Rossellini. It is sad to have to say of a director who has given us notable, even if overrated, films such as Roma città aperta and Paisà what we have to say. But it is also incomprehensible how an artist can reach similar disequilibria in his work, stooping to such infamies as Viaggio in Italia. In this film, there s no subject, no dialogue, no script, no direction. It is a jumble of images that revolve around emptily, tediously, without the slightest glummer of interest. ... Viaggio in Italia is more than an ugly film. It is a true and proper insult to the intelligence of the audience."

By 1953, the critical establishment in Italy had turned against Rossellini for a variety of reasons. Conservative critics and some Catholic writers were incensed by Rossellini’s private life and his scandalous liaison with Ingrid Bergman, although in France, Catholic critics were not puritanical conservatives and championed his films. Leftist and progressive critics did not jump to Rossellini’s defence, as they might have done for other artists, because they were disturbed by Rossellini’s turn away from strictly socio-economic themes with an overtly ideological slant. Thus, critics on both the Left and the Right reacted negatively to the most original aesthetic contributions of Rossellini’s new introspective cinéma.

The glowing tributes to Rossellini in France were also motivated by something more than intelligent recognition of the innovations of these films. Most critics tend to praise the kinds of films they themselves like or would make if they could, and the tributes to Rossellini by writers associated with what would eventually become the French New Wave and with the journal Cahiers du Cinéma were often the reflection of other polemical issues these intellectuals were debating at the time. In 1958, in one of the periodical votes on the all-time best films, which French critics love so much, Rossellini’s Viaggio in Italia was ranked third behind Murnau’s Sunrise and Renoir’s The Rules of the Game but ahead of Eisenstein, Griffith, Welles, Dreyer, Mizoguchi, Vigo, van Stroheim, Hitchcock, and Chaplin by voters that included Andre Bazin’ Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, and Erich Rohmer. In Rivette’s assessment of the film for Cahiers du Cinéma, he made the most famous of all such comments on the film, remarking that "if there is a modern cinéma, this is it," and that "with the appearance of Viaggio in Italia, all films have suddenly aged ten years." Erich Rohmer declared that the public’s negative reaction to the film paralleled the reaction of an ignorant public to impres-sionist art or the modernist music of Stravinsky: "As deliberately as Manet’s refusal of chiaroscuro, the author of Viaggio in Italia scorns the easy choice — of a cinématic language underlaid with fifty years of use. Before Rossellini even the most inspired and original of film-makers would feel duty-bound to use the legacy of his precursors."

In a letter to Guido Aristarco, the editor of the Marxist journal Cinéma Guano, André Bazin defended Rossellini’s new direction after his neorealist trilogy, making another comparison between film and art: "Neorealism discovers in Rossellini the style and the resources of abstraction. To have a regard for reality does not mean that what one does in fact is to pile up appearances. On the contrary, it means that one strips the appearances of all that is not essential, in order to get at the totality in its simplicity. The art of Rossellini is linear and melodic. True, several of his films make one think of a sketch: more is implicitly in the line than it actually depicts. But is one to attribute such sureness of line to poverty of invention or to laziness? One would have to say the same of Matisse.”

These French writers and the critics and directors influenced by them have always reserved a special place for Viaggio in Italia in their admiration. Godard’s Le mépris (1963) may be based on a novel by Alberto Moravia, but it is aesthetically indebted to Rossellini. Bernardo Bertolucci’s background in film was largely gained from time spent in Paris absorbing the ideas of the group associated with Cahiers, and in his first important film, Prima della rivoluzione (1964), one of his characters, a cinéphile who has seen Viaggio in Italia fifteen times, declares, "Remember, you cannot live without Rossellini."

(...) In an interview given in 1965, Rossellini remarked that the enigmatic ending of his film should be compared to the instinctive reaction of people surprised naked. They spontaneously grasp a towel or draw closer to the people near them in an attempt to cover their nakedness. We must also consider Rossellini’s evaluation of the miraculous epiphany concluding the story, the Joyces’ surprising embrace in the midst of the procession. Rossellini’s interviewers asked if the film did not, in fact, have a "false happy ending," and Rossellini’s reply, mistranslated in the often-cited Screen interview, was an immediate "of course, it’s a very bitter film, isn’t it, after all?" In fact, it seems that Rossellini intended the kind of enigmatic and open-ended final sequence so typical of the works of other Italian directors of the period, especially Michelangelo Antonioni and Federico Fellini. Although his intentions may not be completely realized in the final sequence, his comments leave no doubt that the director did not see the sudden epiphany at the close of the film as the final word in the relationship of the English couple. That this is the case may also be deduced from the fact that it is not the embrace that ends the film but, instead, a rather inconsequential shot of a member of the village band, as if the director meant to undermine any obviously positive interpretation of the couple’s reconciliation.

Viaggio in Italia will never become a popular film. Rossellini’s avoidance of traditional dramatic construction with its increase of narrative suspense toward a resounding climax, the flat delivery of the English dialogue and the essentially antitheatrical acting style of his cast, his long takes and avoidance of climactic editing techniques, and his emphasis on minute psychological nuances in the lives of vapid and superficial protagonists will never result in box-office appeal in any commercial cinématic culture. But Rossellini’s innovations in cinématic narrative, even if not always quite so original as the enthusiastic French critics of the Cahiers du Cinéma group claimed, nevertheless represented an important alternative to the dominant cinématic language of Hollywood. A new generation of young filmmakers applauded his efforts to transcend established narrative structures, which were all too closely linked to the dramatic conventions of traditional film and literature. Italian neorealism had largely ignored psychological realism in an attempt to show how environment shaped character during the immediate postwar period, when unemployment and the reconstruction of Italy were the most important central facts of life. Rossellini’s Viaggio in Italia helped to move Italian cinéma back toward a cinéma of psychological introspection and visual symbolism where character and environment served to emphasise the newly established protagonist of modernist cinéma, the isolated and alienated individual.

Peter Bondanella: The Films of Roberto Rossellini.

Cambridge 1993, p. 98-100, 110-111

|

|

Director: Roberto Rossellini

Screenplay: Vitaliano Brancati, Roberto Rossellini

Producer: Roberto Rossellini

Executive Producer: Mario del Papa, Marcello d’Amico

Director of Photography: Enzo Serafin, A.I.C. (b/w)

Original Music: Renzo Rossellini

Film Editor: Jolanda Benvenuti

Sound: Eraldo Giordani

Production Design: Piero Filippone

Costume Design: Fernanda Gattinoni

Production Companies: Les Films Ariane / Francinex / SCG / S.E.C. / Sveva-Junior / Italia Film

Distributor: Fine Arts Films (1954, USA) / Titanus Film Sp.A. (Italia) / UFA (BRD)

Runtime: 79 min (Italia) / 97 min (USA) / 81 min (BRD)

Cinematographic process: 35mm Spherical, Black and White, 1.37:1 Academy Ratio

Sound Mix: Mono

Filming Locations: Naples, Campania / Titanus Studio

Release dates: 7 September 1954 (Italia) / 9 November 1954 (BRD)

|