![]() ChiaroScuro presents

ChiaroScuro presents

![]() ChiaroScuro presents

ChiaroScuro presents

(Stairway to Heaven [USA] | Question de vie ou de mort | Irrtum im Jenseits)

|

|

|

|

|

|

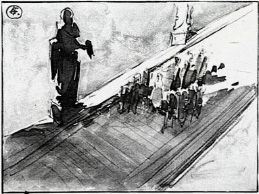

"'A stunning, subversive masterpiece' (Ian Christie), this legendary (and more than a little bizarre) Powell and Pressburger tour-de-force stars David Niven as destined-to-die British aviator who, by angelic mistake, escapes certain death, and lives to falls in love with a young American woman (played by Kim Hunter). When the mistake is discovered Upstairs, a celestial tribunal is convened to decide the hero's fate: will he be allowed to remain on earth, or must he make haste to heaven? The film was commissioned by the British Ministry of Information, to enhance British-American relations, and was screened at the first-ever Royal Film Performance. The jaw-dropping production design, by Alfred Junge, includes a mammoth stairway-to-the-stars, peopled by history's dead. In what was perhaps a playful jab at prevailing cinematic norms of realism, and at socialist ideas of utopia, the film reverses Wizard of Oz colour-coding by presenting life-on-earth reality in sumptuous Technicolor, while the afterlife in heaven is rendered in blander black-and-white."

— Pacific Cinémathèque Pacifique Vancouver

"One of Powell and Pressburger's finest films. [...] it emerges as an outrageous fantasy full of wit, beautiful sets and Technicolor, and perfectly judged performances. [...] What makes the film so very remarkable is the assurance of Powell's direction, which manages to make heaven at least as convincing as earth. [...] But the whole thing works like a dream, with many hilarious swipes at national stereotypes, and a love story that is as moving as it is absurd. Masterly."

"A fantastical, visionary and oddly elusive work, A Matter of Life and Death excels in almost every way without ever losing sight of its humanity. [...] In a genre prone to whimsy and superficiality, that of fantasy-romance, they bring a solidity, a feeling of depth. By standing within their film, rather than to one side, their total belief is apparent; our temptation to second-guess the story, or to treat it as a joke, is hence greatly reduced. Such an appreciation is greatly aided by the wonderful cast of British and American actors. Whether they're in the foreground or the background, the case for several of the heavenly sequences, all contribute to creating a convincing atmosphere. The key is that P&P always have little scenes playing behind the main characters; they entertain the eye without distracting it. In fact this is a theme which runs throughout the film. Aided by Alfred Junge's production design, P&P feel free to be visually adventurous, to go for sights never before imagined. Yet while they push the limits of the technically possible, their efforts are hidden from us. Thus, like the boundary which separates the two worlds, everything within A Matter of Life and Death feels natural. These effects, combined with Jack Cardiff's photography, make the film a richer experience. You could quite safely say that the performances in A Matter of Life and Death are excellent and you'd be right. That is, however, a quite inadequate description, it misses the essence of what makes A Matter of Life and Death special. To capture this you need to think in wider terms, such as the difference between a roaring log-fire and a humming, single-bar electric fire. Both give out heat and ward off the cold, but only one engages all of your senses. Stand close to a real fire and your skin turns to parchment under the shifting blaze, sparks erupt around you and the stinging smoke invades your sinuses. This is what you experience with A Matter of Life and Death; compared to films that engage on a single level, the power here is awesome, almost frightening."

"A Matter of Life and Death began production on the day the Japanese officially surrendered to Douglas MacArthur. ... The production of A Matter of Life and Death was the largest attempted in British cinema since The Thief of Bagdad, and, as always with an Archers film, the look was carefully worked out before production. ... The film ultimately fails for the very reason it had been created: to demonstrate the historical bond between the United States and England. The Archers did a disservice to themselves by having the matter settled in a courtroom, because this allowed for only a static milieu as Powell had learned in The Night of the Party. For all of this film’s technical advancement, the Archers have only slightly more success here. Powell always disparaged of lengthy dialogue sequences, and in Pressburger, a writer whose rhythmic style of writing emphasizes the image as much as the spoken word, he found his perfect companion. Once the two attorneys take up their positions, the film is overwhelmed by dialogue and ideology. Even Powell conceded that he was not "happy about the ending, but that’s the relic of the propaganda period—the request of the M of I.”

"A Matter of Life and Death, was released in the US in 1947 under the title Stairway to Heaven, a title Powell always disliked. Kim Hunter saw the restored version last fall at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and remembered that, at the time, some great movie mogul insisted Americans would never go see a film with death in the title so it was changed for the US release. [...] In 1995 the British Film Institute released a version of the film that had some restoration work done on it. According to Grover Crisp, V.P. of Asset Management and Film Restoration at Sony Pictures they were not satisfied and hence the desire to fully restore the work. Undertaken in July of 1999, Sony, in cooperation with the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences and the British Film Institute, began the restoration which was completed a year later at a cost of around $150,000.00. The process was all photochemical and only the soundtrack was remastered digitally. "The color sequences," says Crisp, "have a vibrancy and a palette that people haven't seen in quite some time." [...] "The key collaborators are the laboratories. They are the unsung heroes of film restoration," said Crisp. A Matter of Life and Death was done at the YCM Lab in Burbank, CA and the soundtrack was remastered at Chace Productions. According to Crisp one of the biggest challenges in film restoration today is the instability of the new digital technology. Because no two films are exactly the same it's trial and error. What couldn't be done three years ago in some cases, can be accomplished today. [...] The challenges are often daunting and the technology continues to change rapidly. "Digital," claims Crisp, "is unreliable, takes time and increases costs." A Matter of Life and Death had challenges of its own. The British Film Institute provided the technicians with the camera negative for the three-strip Technicolor film. They discovered that when the original film was edited the three strips were slightly out of alignment. Although this was less of the problem in 1946, it became more of problem in 1999 when in addition to the misalignment, the technicians found that the three strips had shrunk in the ensuing 50 plus years. Adding to the challenge was the fact that each strip had shrunk at a different rate. There are a few moments when the film looks slightly out of focus but all in all the color sequences are impressive. The team was further tested, surprisingly, by the black and white sequences. There was no original black & white negative from the film, which was apparently cut together with duplicate negatives. The delicate process involved shooting a new positive of the black and white with black and white film stock. From the positive three separate fine grain negatives were made. The team then discovered that the original black & white negative had it's own set of defects which transferred to the three newly printed negatives. However, not all the negatives had inherited the same defects. It became clear that it was impossible to cut the three new negatives together because of the varied defects, and in the end they chose the best of three b&w negatives and cut it into the new film."

|

|

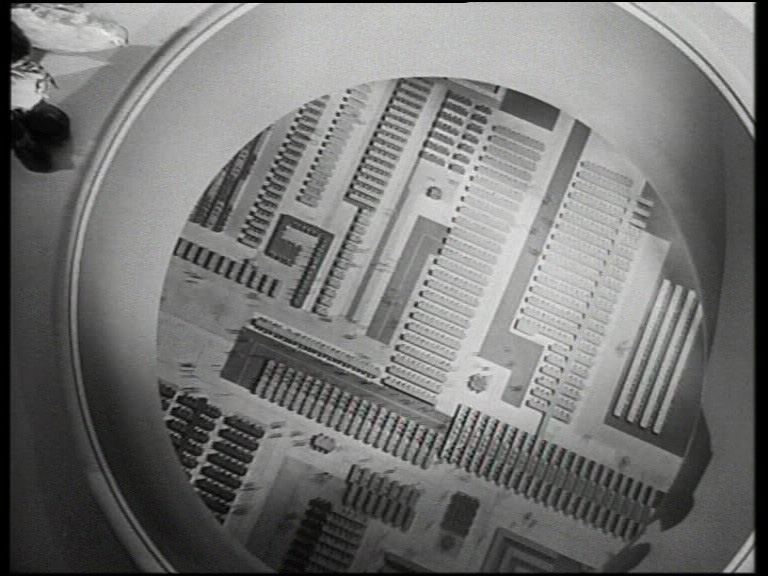

Jack Cardiff, Michael Powell and David Niven (left) | Production design (right)

|

|

||

|

Distribution:

|

Carlton Home Entertainment Region 2 |

|

|

Runtime:

|

99:58 min (PAL Speedup + 4% = 104 min) | |

|

Video:

|

1.30:1/4:3 FullScreen Average Bitrate: 4.99 mb/s, 3.84 GB PAL 720x576 25.00 f/s |

|

|

Audio:

|

• English Dolby Digital 3.0 Mono | |

|

Subtitles:

|

None | |

|

Features:

|

• Jack Cardiff Interview (09:54 min)

• Cast/Crew Biographies |

|

| DVD Release Date: 14 September 1998 Keep Case Chapters: 13 DVD Encoding: PAL Region 2 (EU/UK) 1xSS-SL/DVD-5 (4.30 GB) |

||

|

Comment:

|

This was one of the earliest Carlton DVD releases, dating back to 1998, and, considering the state of art of DVD production at that time, it is still a good and clean transfer with occasional shimmering from a slightly faded Technicolor print. In 2000 however, a new restauration supervised by the Academy Film Archive and Sony Pictures Entertainment in collaboration with the British Film Institute Collection's National Film, Television and Video Archive was screened at London's National Film Theatre and at the Academy's Samuel Goldwyn Theatre in Los Angeles. A DVD release of this restauration is due to be released by Sony/Columbia Tristar, hopefully as an opulent special edition worthy of the filmmakers involved.

Film: ***** out of ***** |

|

|

Frame 1

(PAL 768x576)

|

Frame 2

(PAL 768x576)

|

Frame 3

(PAL 768x576)

|

Frame 4

(PAL 768x576)

|

Frame 5

(PAL 768x576)

|

Frame 6

(PAL 768x576)

|

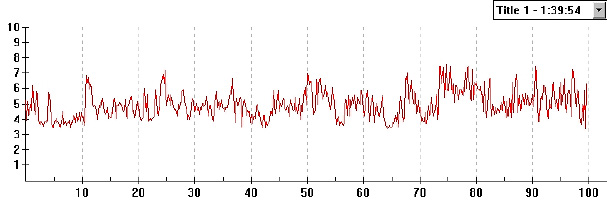

Average Bitrate :

4.99 mb/s

The Vertical axis represents the bits transferred per second. The Horizontal is the time in minutes

|

This is a strictly non-professional and non-commercial DVD review. Don't expect industry reference work! All ChiaroScuro captures are taken under MacOS X using VideoLAN and Snapz ProX. For further methodological remarks see DVDBeaver (click on "Methodology"): "We are not a lab and are doing a good a job as our time and energy permits. Thank you for understanding." |