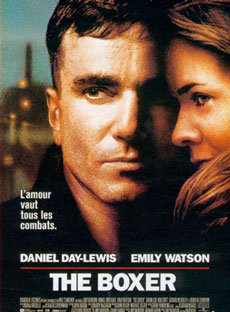

Danny Flynn (Day-Lewis) returns to Belfast after 14 years in prison for IRA activity. He's an outcast castigated by a former boxing colleague Ike (Stott) for having wasted his talents; by old flame Maggie (Watson), now married to a jailed terrorist for the ruin of their relationship; and by Republican militants for having renounced violence outside the ring. Despite the disapproval of Maggie's son and father (Cox), a peace seeking Republican leader who views the resumption of their affair as personally and politically dangerous, Danny and Maggie find themselves drawn together again. Moreover, Danny teams with Ike to set up a gym where training and bouts ignore the sectarian divide. But even love and the most modest projects can fall foul of ingrained prejudice. This may not offer a hugely original take on the Troubles, but it does deliver dramatically. Day-Lewis, taciturn and strong-willed, is as persuasive as ever, while Stott and Cox offer strong support. While Sheridan (who co-wrote) weighs in with gutsy, gritty direction, shooting the fight scenes with panache and cutting sharply throughout for suspense and pace. Politically, too, it's sensitive and sensible.

Nach seiner Haftentlassung will sich ein ehemaliger IRA-Aktivist ausschließlich dem Boxsport widmen und sich aus allen politischen Konflikten heraushalten. Diese Haltung macht ihn suspekt, und er gerät zwischen die Fronten von Waffenstillstandsbefürwortern und militanten Aktivisten, die ihre Ziele mit Bombenterror durchzusetzen versuchen. Ein ebenso ernsthafter wie aufrichtiger Film, der das Leid und Elend eines durch Bürgerkrieg zerrütteten Landes zeigt und sich vorbehaltlos dem Pazifismus verschrieben hat. Effektvoll inszeniert und überzeugend gespielt.

Lexikon des internationalen Films

The Boxer marks the third collaboration between director Jim Sheridan and actor Daniel Day-Lewis. (Day-Lewis also starred in Sheridan’s In The Name Of The Father and My Left Foot, winning and Academy Award for his performance in the latter film.) It is a tale that star Emily Watson describes as "strong, gritty, kind of warts-and-all", explains Emily Watson.

Women factor into The Boxer more prominently than in most films centered on such a brutal sport. Echoing a theory from Joyce Carol Oates in her book On Boxing, Sheridan is fascinated with the loyalty Maggie’s community of women express for the underdog, whereas men more readily switch allegiance to whomever is winning. "In this film, women characters are not peripheral to the action", Sheridan says. "But like the Irish in general, they stand by the victim. They love when Danny’s in the ring and they can say, ‘we might beat England for just one hour.’" Equally important, women in are ruled by the code that exerts tremendous influence in the oppressed culture of Northern Ireland.

Ireland — the code of the prisoner’s wife. "The men inside the prison feel that if the women aren’t loyal to them, the morale of the army would collapse, so all the women are watched in a kind of self-censorship", explains Sheridan. "Their every move is being watched because of the impact it can have. There is no privacy in this war." "In many ways, this is a film about the emergence of women in this society," he adds. "It’s about love and the feminine coming into the society—the gentle."

As a springboard for script, writer George referred to Sheridan’s screenplay about the life of Irish World Featherweight Boxing Champion Barry McGuigan, who later became actor Daniel Day-Lewis’ boxing trainer during filming. But the story evolved into a purely fictional piece and, true to Sheridan’s fluid, spontaneous style of directing, the script continued to change throughout shooting.

Known for working in close partnership with actors, Sheridan explains his philosophy: "I essentially think that great acting is also great scriptwriting—but this isn’t as anarchic as it seems. If a story becomes really structured, I fear it will be too predictable. On the other hand, if an actor has to fight for the character, then it becomes a mixture of the actor’s perceptions and mine." After starring in two other Sheridan films, Day-Lewis is especially attuned to this approach. "We both went into this willing", he says. "You’re telling a story, but don’t really know its outcome. That unleashes a huge degree of insecurity which is quite useful to us both."

In fact, as creative spontaneity increased on the set of , the film took on more and more of the distinctive feel of a Sheridan effort. "I see so many films that are planned out ahead of time and never work", says Sheridan. "When film gets closer and closer to documentary—closer to whatever happens and farther away from opera, in which everything is organized—then it seems to kick in."

Shot on location in Dublin over 16 weeks, incorporates urban environments reminiscent of Belfast, where the story takes place. Some scenes were shot in a district of old derelict flats similar to bombed-out neighborhoods in the troubled North. Others took place near Sheridan’s childhood haunts: Maggie’s house in the film is next door to the one in which Sheridan was born.

Also in the interest of realism, the cast researched the harsh personal side of "The Troubles". Emily Watson visited Belfast with Terry George’s brother, driving through hard-hit areas, talking to residents and meeting prisoners’ wives. The process allowed her to develop a back story for her character, Maggie. "Once you’ve got the structure of the place where your character lives and the political and social background, then it’s an imaginative process", explains Watson. "At the beginning of the film, Danny and Maggie haven’t seen each other for 14 years, and they were desperately in love as teenagers. What you create are all those memories to use as a reference point."

Finally, the actors adopted appropriate physical attributes, ranging from the moves and physique of a boxer, in Day-Lewis’ case, to characteristically Northern Irish accents. Fourteen-year-old Ciaran Fitzgerald, who portrays Maggie’s son, Liam, shifted easily from his own more southern lilt and learned boxing footwork as a prerequisite to the choreographed fight he takes part in.

Last year Day-Lewis, already in training as a boxer for three years, stepped up his efforts in preparation for filming. For two years prior to filming, and about six months during production, Day-Lewis was coached by the champion who originally inspired Sheridan’s story, Barry McGuigan.

"Barry is a gentleman of the ring", says Day-Lewis. "What is deeply moving to me is that he had tremendous respect for the people he was pitted against, like bullfighters in the past: purity, dignity and respect between two separate beings." Yet McGuigan’s raw, unfiltered drive to fight showed in the relentless training he put himself through and in the fact that even after a hard day’s work, it was so much in his blood, the fighting itself, that he was still up for the scrap. While McGuigan acknowledges he trained like "a madman", he also describes Day-Lewis as equally driven. "Daniel and I are alike in that way", he says. "We both believe that you only get out what you put in. It’s Daniel’s nature that he doesn’t do anything easily, so he trained incredibly hard. He actually lived the life of a fighter."

Day-Lewis stayed in fighting form the entire 16 weeks of the shoot, to accommodate the three matches at the film’s beginning, midpoint and end. "It was grueling to keep such an unnatural level of readiness", Day-Lewis explains, "because athletes go through peaks and troughs, working toward a level of fitness where you’re razor sharp for the moment itself, then burning yourself up in the event." McGuigan reports, however, that Day-Lewis was "the most determined person I have ever met. He’s a chameleon. He molded himself. I’ve worked with fighters who haven’t trained half as hard. And this guy can truly fight. I’m a commentator for fights around the U.K. now and I know all the middleweights, but I can say that he could fight, right now, any of the top ten in the country. If I’d had him at 19, I would’ve made a world-class fighter of him." The combination of McGuigan’s coaching, Sheridan’s direction, George’s psychologically insightful script and Day-Lewis’ tenacious immersion in his role created a subtle and quietly potent title character with, in Sheridan’s words, "a silence at the center."

Day-Lewis describes the extreme introversion of Danny’s time in prison as running a close parallel to boxing itself, an activity that does not require words but weaves an entire secure world all its own. The sport can be comforting in the way that a prison cell can have something comforting about it after 14 long years, providing a known place with well-defined, simple boundaries and rules.

McGuigan refers to the gymnasium as a sanctuary. "When everything else is going crazy around you, you can punch the bag, spar—get rid of all the tension in your life and in your head, he says." "In the ring, Danny’s fighting within the rules", explains Sheridan, "hoping that if he stands up and fights fair it will draw people naturally to the nobility of the fight. On the other hand, when fighting moves from, say, war into terrorism, it does so because people have lost the rules and lost a vision of what they want the future to be. Danny has a positive view of what can be achieved by staying within the rules."

In a related thematic undercurrent, the film explores the nature and the limits of human fear. "Boxing brings fear out into the open in a very clear way", notes Day-Lewis. "It puts you in an enclosed space where you confront things that are fearful, face-to-face with someone trying to hurt you. Most fighters won’t really talk about that because so much of it is about dominating the fear long before they ever reach the fight situation, to such an extent that the appetite completely eclipses the fear." "At least with boxing, the enemy is out there—outside yourself", adds Sheridan. "Most people are trying to be normal and prove that they’re calm and cool, when, in fact, we’re all in terror all the time anyway." "Boxing forces the fighter to answer his innermost fears and feelings", says McGuigan. "An example of this is when Danny must choose between winning the big London fight and pummeling his opponent." "You must face questions about your courage, your nature", McGuigan continues. "Ultimately, it’s about character. Ninety percent of the people in boxing are great guys, very ethical and upstanding. The training and the conditioning of your own mind makes all the difference. It makes you a better person."The BoxerThe BoxerThe BoxerThe BoxerThe BoxerThe Boxer

Emily Watson as Maggie

Since boxing is so much about the internal dynamics of the individual, the bond between trainer and fighter is a particularly close one. "It requires complete trust", McGuigan explains. "The trainer knows not only every detail of your moves, but your behavior and innermost thoughts, as well. There are no secrets between a trainer and a fighter." The trainer is like a mentor or a teacher, according to Sheridan, which adds to the enormous audience appeal of Ken Stott’s character, Ike Weir. To portray Ike, Stott spent time with an Irish trainer and some of his charges, learning the ways of that close relationship. But, as in other films where boxing has played a major role, the trainer in has a personal flaw. "Whether it’s drinking or a physical impairment, Ike Weir is somebody who represents us because he’s not physically up to fighting the way the boxer is", explains Sheridan. "So we empathize with the person who’s trying to help."

Sheridan calls Day-Lewis’ performance "smoldering. You get to know the private world of him, and you ascribe your own reasons to his actions. It’s not as driven as Daniel’s work in, say, In The Name Of The Father." But if Danny resonates on a powerfully internal level, then the character of Maggie is like a stifled ember exposed to oxygen. "She’s very strong and she’s very weak", says Watson of her character. "She’s been brought up within the political structure of the IRA, her father is head honcho and she’s very much played the role. As the ideal prisoner’s wife, she must behave in an exemplary fashion, but suddenly she begins to realize that’s not what she wants to be or do. She’s forced to choose what she wants, to grow strong, really." Watson has been described by Sheridan as "very generous and very giving, precisely the qualities that were needed to complement Daniel’s character, who is very quiet and withdrawn. It was a perfect match and good charisma."

No less a love story than a pugilist’s tale, has an arguably classical theme: Danny and Maggie experience a fateful love discountenanced by society, and from that discord arises drama. "The funny thing is that once something becomes a love story, it can lose the drama", says Sheridan. "Drama is conflicting stories at play and love stories are about the conflict being over." "There’s even something almost mundane about Maggie and Danny’s relationship under any other circumstances. But it becomes absolutely extraordinary in this kind of cage that they’re living in, and the drama in keeping them apart is what’s most interesting", Sheridan adds. "Their contact is mostly through their eyes and a big part of their relationship is being comfortable in silence together. In the end, you feel they just have to be together to survive. So in the middle of this crazy boxing tale and violent war story, the film is actually very gentle at heart."

In fact, Sheridan seems drawn to exploring fundamentals like love, allegiance and human dignity in settings as violent as Northern Ireland and the boxing ring. "When you describe just the physical side of boxing", he says, "then what’s missing is a spiritual dimension, a spiritual quality that occurs when people have to go through bad experiences and undergo change." "But the outstanding people, the people who link one era to another, will always have that quality", concludes Sheridan.

Daniel Day-Lewis as Danny Flynn

Michael Collins

Sheridan called on the two-time Academy Award-winning British cinematographer Chris Menges, ASC, BSC (The Killing Fields, The Mission) to serve as director of photography on The Boxer. Ironically, Menges had just completed filming on director Neil Jordan's own IRA-themed film, the historical epic Michael Collins (see AC Oct. '96), which also earned him an Oscar nomination. The veteran cinematographer, who has directed four films (including A World Apart, Second Best and the upcoming release The Lost Son), once again found himself shooting on location in Dublin, Ireland, which doubled for British-controlled Belfast in The Boxer.

When asked to compare his approaches to the back-to-back IRA-themed films, Menges offers, "Michael Collins had an enormous history behind it. The clothes, the people, the time and the man's life immediately conjured up a graphic image of how the film should look. We were dealing with early 1900s carbon lights in the streets of Dublin, so there was a definite period image that I was inspired to capture. The Boxer was shot from the perspective of standing back and catching the story in a documentary style. The look of the film developed organically, but the two words Jim did stress before we started were 'freedom' and 'reality.'

"In documentaries, you tend to stand back with an 50mm or 80mm lens, so that you're less obtrusive while shooting and the microphone can float in close. There's a chance that you will be at least ignored, if not forgotten. Then you have a chance to catch 'the moment,' or something special, which is the biggest reward if you're perceptive with a handheld camera. On The Boxer, we shot a lot of scenes with two Moviecam Compact cameras with long lenses, running simultaneously to lend added fluency to the performances. It's a different kind of storytelling. I think if that style is used skillfully in a feature, it does liberate the actors. The Boxer is a totally performance-driven story, and a work of passion."

Menges bathed the Northern Ireland scenes in The Boxer in cool, blue tones, a bold approach inspired by the color philosophies of Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC. "I remember talking to Vittorio about light," Menges says. "He would talk about [the psychology of] the rich [colors], the warmth, the sun, the heat of Italy. When you're in Northern Ireland, there are days of great clarity, but also days of pollution, gloom and clouds. Northern Ireland has that 'blue' quality. We've been shooting in Arizona for The Lost Son, and the colors are so vibrant and different. When you're in Northern Ireland, very often there are rain clouds and a different kind of feel. As a cinematographer, you're always trying to capture the true sense of light that exists in certain places."

In rendering the real look of Northern Ireland forThe Boxer, Menges used almost no filtration on his Zeiss lenses, and shot predominantly on Eastman Kodak's 500 ASA 5298 film (save for a few bright daylight scenes shot on 5248). "I would always try to make very simple decisions about the light and the camera," he comments. "This was a film about listening to the words. [For the Northern Ireland day exteriors], I would usually just use the available light with reflectors, unless it was just too gloomy or dull."

Menges extended his less-is-more, documentary-style approach even to somewhat dark interiors, such as the warm, inviting pub where many of the story's tight-knit West Belfast community residents go to unwind. "I used almost all practical lights in the pub, because the main goal was the freedom of the camera," Menges says. "[Production designer] Brian Morris gave us the atmosphere of a real pub designed in the 1950s, and we added the set onto the flats we were shooting in. The practicals were little lampshades on a wall and tungsten lights above the bar. If there was trouble on a particular shot, I would sneak lights into a corner, but they would be nothing fierce maybe 500-watt tungsten quartz bulbs going off reflectors or [through] tracing paper."

The narrative of The Boxer is framed around three key boxing matches, which are all given a distinct visual look by Menges. The filmmakers dedicated much thought to methods of freeing the camera within the claustrophobic confines of the boxing ring. "In preparing for the boxing scenes, we certainly watched many fine films, such as Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull, which I studied hard and diligently," Menges says. "In the end, we suspended a woven rubber bungee cord about 26' above the boxing ring. Imagine a pendulum in the middle of the boxing ring: on the bottom of this woven rubber fabric, we placed a flat bar upon which we mounted the camera. Then we ran all of the camera's controls the iris, the focus, the video as well as a cable that adjusted the tilt of the small video monitor that was mounted beside the camera. All of these cables ran up to the ceiling and across to a balcony, where the focus puller had his control, an assistant adjusting the iris was on another and a person tilting the television monitor manned a third. Operator Mike Proudfoot or I would operate the bungee cord. It made for a very free camera that could float all the way around the ring without restrictions. It was a great sensation and it made Jim laugh."

Menges again favored the cool, bluish end of the color spectrum for the film's first boxing match, set inside an old, fluorescent-lit boxing gym that Flynn has renovated after being released from prison. Before the match, however, parents of children killed in "the troubles" are acknowledged from the ring, and Menges decided to create an appropriate contrast by accenting the parents with warmer, more amber tones. "We did a lot of research to try to get the look of Belfast as accurate as possible, so we visited several gyms and looked at lots of pictures," he says. "We lit the boxing ring with eight 6'-long, flicker-free fluorescent tubes suspended on wires from the ceiling. Those tubes were quite cold in color. For the audience members, we used 500-watt Pars in black steel industrial lampshades, which shone straight tungsten light on them probably at 2800° Kelvin."

The emotional stakes are raised higher for Flynn's second boxing match, which takes place in the center of a teeming, capacity West Belfast audience. "We shot in a huge Dublin church hall with a very high ceiling, where the light responded in a very different manner," Menges recalls. "Also, our use of the light was different. For instance, there was blue light coming in the windows, and it was almost dark high up in the auditorium. We used 6K HMIs outside the windows, and I used a system of tungsten bulbs eight feet above the ring. The light on the audience was reflected from the center of the ring. That gave the camera maximum freedom, since it meant that there were very few lighting fixtures around the room. We were free to film in a verité style. If you surround the action with lamps and light stands, you'll never be able to 'capture the moment.' The light from the center of the ring glowed upward into the people in the [staggered] seating tiers.

"The lights above the ring were controlled by dimmers, which I used throughout the shoot. The other tool I used throughout the boxing scenes was the diaphragm of the camera. I was operating the camera for the second boxing match, so I had one of my assistants pulling stop from about T8 in the middle of the ring to T3 on the edges of the ring. But for the other two matches, when I wasn't operating I would control the aperture all the time on a radio."

The penultimate match in The Boxer was filmed within a vast soundstage at Ardmore Studios near Dublin. The space was dressed to re-create the ballroom of London's historic Grosvenor House Hotel. The cold, stark look of the previous two matches is replaced by the warm, stuffy atmosphere of the London hotel, which is populated by well-fed, blasé patrons in full evening dress. Menges explains, "There were twelve 500-watt tungsten bulbs in steel stage-light boxes on each of the four corners of the ring, which ran the whole length of the sides of the room. The bulbs were slightly warm and produced a yellowy glow which was quite reminiscent of what you would see in the real hotel. They're very powerful lights, so they gave us an amazing T5.6 aperture at 500 ASA. The idea of the scene was to make the light hot. We shot with the suspended camera on the bungee cord from the ceiling, but we also worked handheld and with a Steadicam and a regular dolly. There were always three cameras running simultaneously for the boxing scenes, unless we were using the 'bungee camera.'

"To light the audience, we basically used the practicals on the tables around the room, as well as a few 10Ks and 5Ks. Plus, there were chandeliers, mirrors and lights suspended from the walls Brian Morris built a very fine duplicate of the original Grosvenor House Hotel, and the crew really helped me out. I have to say, I had great Irish crews on both The Boxer and Michael Collins."

Menges attributes the film's timeliness to director Sheridan's tenacity and his willingness to abruptly alter his script according to the then-shifting political situation in Northern Ireland. "Jim is an incredibly demanding director," he admits. "He gets images in his mind as fast as lightning, and you have to run to catch up. The script was still being written as we shot it, because the political situation in Northern Ireland was changing rapidly. We had to shoot new scenes as the politics changed, because Jim was trying to make a film that honestly had meaning in understanding [the current political situation] in Ireland. We're never going to solve the problem until we first at least understand it, which is why The Boxer was an important film to work on. Like , it was an Irish film that I, being from Britain, am really proud to have worked on."

American Cinematographer, June 1998

|

|

Director: Jim Sheridan

Screenplay: Jim Sheridan, Terry George

Producer: Arthur Lappin, Jim Sheridan

Associate Producer: Nye Heron

Director of Photography: Chris Menges, B.S.C. (Technicolor)

Original Music: Gavin Friday, Maurice Seezer

Film Editor: Clive Barrett, Gerry Hambling

Sound: Kieran Horgan (mixer)

Casting: Nuala Moiselle

Production Design: Brian Morris

Art Direction: Fiona Daly, Richard Earl

Costume Design: Joan Bergin

Makeup: Maire O'Sullivan

Hairdesign: Anne Dunne

Stunt Coordinator: Patrick Condren

Boxing Consultant: Barry McGuigan

Special Effects: Yves De Bono

Production Companies: Universal/Hell's Kitchen

Distributor: Universal Pictures (USA / United International Pictures (UIP) (Argentina, France, Spain, Germany)

Runtime: 113 min (3189 m)

Cinematographic process: Technicolor, 35mm Spherical, 1.85:1 Widescreen

Sound Mix: DTS / SDDS

Filming Locations: Dublin, Ireland / Production Dates 1 April 1997 - 19 July 1997

Release dates: 19 December 1997 (USA) / 19 February 1998 (Germany, Berlin film festival) / 6 February 1998 (Eire) / 20 February 1998 (UK)

Awards: American Society of Cinematographers 1998 Nominated ASC Award Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography in Theatrical Releases Chris Menges // Berlin International Film Festival 1998 Reader Jury of the "Berliner Morgenpost" – Jim Sheridan; Nominated Golden Berlin Bear – Jim Sheridan // Golden Globes 1998 Nominated Golden Globe Best Director – Motion Picture Jim Sheridan; Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama Daniel Day-Lewis // Goya Awards 1999 Best European Film Jim Sheridan

|