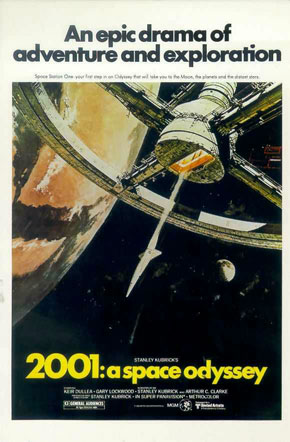

A mind-bending sci-fi symphony, Stanley Kubrick's landmark 1968 epic pushed the limits of narrative and special effects toward a meditation on technology and humanity. Based on Arthur C. Clarke's story "The Sentinel," Kubrick's and Clarke's screenplay is structured in four movements.

At the Dawn of Man, a group of hominids encounters a mysterious black monolith alien to their surroundings. To the strains of Strauss' "Thus Spoke Zarathustra," a hominid discovers the first weapon, using a bone to kill prey. As the hominid tosses the bone in the air, Kubrick cuts to a 21st- century space craft hovering over the earth, skipping ahead millions of years in technological development only to imply that man hasn't advanced very far at all psychologically. U.S. scientist Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester) travels to the moon to check out the discovery of a strange object on the moon's surface: a black monolith. As Floyd touches the mass, however, a piercing sound emitted by the object stops his fellow investigators in their path. Cutting ahead 18 months, impassive astronauts David Bowman (Keir Dullea) and Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood) head towards Jupiter on the space ship Discovery, their only company three hibernating astronauts and the vocal, man-made HAL 9000 computer running the entire ship. When the all-too-human HAL malfunctions, however, he tries to murder the astronauts to cover his error, forcing Bowman to defend himself the only way he can. Free of HAL, and finally informed of the voyage's purpose by a recording from Floyd, Bowman journeys to "Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite," through the psychedelic slit-scan Star-Gate to an 18th century room, and the completion of the monolith's evolutionary mission.

With assistance from special effects expert Douglas Trumbull, Kubrick spent over two years meticulously creating the most "realistic" depictions of outer space ever seen, greatly advancing cinematic technology for a story expressing grave doubts about technology itself. Minimizing dialogue and surrounding his space travelers with sterile, machine-ridden environments, Kubrick depicts a future world devoid of signs of "humanity," save for banal conversation and predatory impulses. With its narrative ellipses and emphasis on evocative, poetic imagery like a spacecraft "waltz" choreographed to "The Blue Danube," 2001 forces the viewer actively to elicit its meanings--and not be as passive as Bowman and Poole—while simultaneously absorbing the dazzling spectacle. Despite some initial critical reservations that it was too long and too dull, 2001 became one of the most popular films of 1968, underlining the generation gap between young moviegoers who wanted to see something new and challenging and oldsters who "didn't get it." Provocatively billed as "the ultimate trip," 2001 quickly caught on with a counterculture youth audience open to a contemplative, i.e. chemically enhanced, viewing experience of a film suggesting that the way to enlightenment was to free one's mind of the U.S. military-industrial-technological complex. While steeped in Kubrick's characteristic cynicism about human fallibility, 2001's innovative visuals and final hopeful message speak to the myriad possibilities for advancement and transcendence. Nothing quite like 2001 has ever come out of Hollywood before or since.

Lucia Bozzola, All-Movie Guide

A characteristically pessimistic account of human aspiration from Kubrick, this tripartite sci-fi look at civilisation's progress from prehistoric times (the apes learning to kill) to a visionary future (astronauts on a mission to Jupiter encountering superior life and rebirth in some sort of embryonic divine form) is beautiful, infuriatingly slow, and pretty half-baked. Quite how the general theme fits in with the central drama of the astronauts battle with the arrogant computer HAL, who tries to takeover their mission, is unclear, while the final farrago of light show psychedelia is simply so much pap. Nevertheless, for all the essential coldness of Kubrick's vision, it demands attention as superior sci-fi, simply because it's more concerned with ideas than with Boy's Own-style pyrotechnics.

Stanley Kubrick's cinematic milestone was in every sense an experimental film, harnessing the widescreen, epic format for an intensely metaphysical, ultimately very personal use. Shot in Super Panavision 70 and presented in Cinerama, 2001 was conceived less as a science fiction narrative than as an experience in space and time. As a re-creation of the dimensions of outer space—taking us beyond deep focus into infinite focus—it has never been matched. Neither has the grace with which Kubrick's pristine visuals literally waltz through several millennia of evolution in a mere two-plus hours of film containing very little dialogue. In this sense, Quest for Fire, while in no way 2001's equal, might be considered a prequel. Kubrick has described 2001 as "nonverbal," adding, "I tried to create a visual experience, one that bypasses verbal pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious with an emotional and philosophical content.... I think that if 2001 succeeds at all, it is in reaching a wide spectrum of people who would not often give a thought to man's destiny, his role in the cosmos, and his relationship to higher forms of life."

A beautiful, confounding picture that had half the audience cheering and the other half snoring. Kubrick clearly means to say something about the dehumanizing effects of technology, but exactly what is hard to say. One of those works presumed to be profound by virtue of its incomprehensibility, 2001 is nevertheless an astounding visual experience—one to be enjoyed, if possible, only on the big screen.

...The screenplay—which is often quite witty, especially in the largely satirical Sylvester sequences—probably was meant sincerely, but has the feel of something that was never thought through. Kubrick seems to have understood that, with the emergence of drug culture and middle-class spiritual yearnings during the late 60s, anything really huge and really vague stood a good chance of being received as something really deep. If so, Kubrick's strategy worked: made at a cost of $10.5 million, the film began to build slowly but eventually took in almost $15 million in North America, then about half that upon rerelease in the slightly shorter version (141 minutes) in 1972. Many hailed it as a religious experience, and underground newspapers counseled readers to time their ingestion of hash brownies so as to be optimally stoned during the psychedelic final scenes. Clarke's short story was first made into a novel, then into the screenplay that MGM financed for $6 million. The budget kept rising, and the studio execs feared a disaster. The casting of Lockwood, Dullea, and Sylvester, three undynamic actors (in these roles), must have been deliberate, as Kubrick didn't want anything in the way of his vision (whatever that was). 2001 continues to annoy and delight audiences; for sheer spectacle, it may be unsurpassed. Its relatively low-tech special effects, masterfully engineered by Douglas Trumbull, remain more astonishing and persuasive than much of today's computer-generated gimmickry.

Stanley Kubrick on the set

The very fact that one attempts to interpret the metaphysical aspects of 2001 is proof of how dramatically Kubrick has liberated the cinema epic from its old outworn traditions of mere bigness and, too often, accompanying banality. The starting and finishing points of his gigantic undertaking are rooted in intellectual speculation. For the first time in the commercial cinema, a film of this cost and magnitude has been used to advance ideas.

To have formulated and, even more, to have retained this intention throughout the years it took to prepare and film it, withstanding all the pressures of time, budget, and collaborators, would be a major achievement for any single filmmaker. But Kubrick has accomplished so much else that is individual and original. The technical marvels of 2001 surpass any before it and are not likely to be overtaken in turn until new techniques of filming are evolved or another director of the same obsessive faculty and skills appears. Nor is it just a matter of successful special effects. The effects are so convincing that we cease to regard them as "special" and look on them as a far more integral part of the film. The effects, in short, become the environment; and this in turn becomes the experience that Kubrick creates and communicates. Of course, all creation involves the idea of communication, whether successful or not. But what makes 2001 so radical a development is the way its structure and imagery have been elaborated organically with its content, so that each contains and extends the other. As well as anticipating the shape of things to come, Kubrick uses his medium to convey the feel of them. There is scarcely an area of intellectual speculation in the film, whether about serial time, computerised life, mechanistic behavior, or evolutionary intelligence, that is not accompanied by a sensory involvement.

2001: A Space Odyssey commands respect as the most impressive feat of filmmaking Kubrick has undertaken to date; but its importance extends beyond what it adds to our knowledge of his outlook and artistry. Above all else, it marks a significant advance in the way of communicating ideas through the medium of film. For its effect is determined as much by the visual properties of the medium through which it is transmitted as by any of the actual events, hypotheses, and reflections comprising the picture's content. By suppressing the directness of the spoken word, by breaking with narrative logic, Kubrick has insured that watching his film requires an act of continuous inference on the part of viewers to fill in the field of attention by making their own imaginative connections. Though as rigorously conceived as any of Kubrick's major films, the whole work leaves the densest impression of images which are free to imply much more than eye and mind take in. The mythical idioms which characterise a great deal of the film's "feel" take supremacy over the old imperatives of the story made up of logical cause and effect. That notorious phrase of McLuhan's, "the medium is the message," has readily suggested itself to some of those who have written about 2001: A Space Odyssey; but it really does not suffice for Kubrick's power to generate a richer suggestiveness than a "message." In his case, one would prefer to say that the medium is the metaphor.

Alexander Walker: Stanley Kubrick Directs.

New York 1972, p. 265-267

|

|

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Screenplay: Arthur C. Clarke, Stanley Kubrick (based on the short story "The Sentinel" by Arthur C. Clarke)

Producer: Stanley Kubrick, Victor Lyndon

Director of Photography: Geoffrey Unsworth B.S.C., John Alcott (additional photography) (Super Panavision 70, Cinerama, Technicolor, Metrocolor)

Original Music: Aram Khatschaturian (from "Ballet Suite Gayaneh"), Richard Strauss (from "Also sprach Zarathustra"), Johann Strauß (from "Blue Danube Waltz"), György Ligeti (from "Atmospheres", "Lux Aeterna", "Adventures" and "Requiem")

Additional Music: Alex North

Film Editor: Ray Lovejoy

Sound: A.W. Watkins, Winston Ryder (sound editor)

First Assistant Director: Derek Cracknell

Production Design: Tony Masters, Ernest Archer, Harry Lange

Art Direction: John Hoesli

Costume Design: Hardy Amies

Makeup: Stuart Freeborn, Colin Arthur (special effects makeup artist ape masks, uncredited)

Special Effects: Stanley Kubrick (designed and directed), Wally Veevers, Con Pederson, Douglas Trumbull, Tom Howard (supervisors), Colin J. Cantwell, Bryan Loftus, Bruce Logan, John Jack Malick, Frederick Martin, David Osborne

First Assistant Director: Derek Cracknell

Production Companies: Hawk / Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer / Polaris

Distributor: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (USA) / MGM (Deutschland)

Also Known As: Journey Beyond the Stars (working title)

Runtime: 156 min (USA premiere cut) / 139 min (USA, final cut) / 149 min (Deutschland, mit Vormusik)

Budget: $10.5m (USA)

Cinematographic process: Metrocolor Technicolor, 65 mm Super Panavision70; Printed film formats: 70 mm Super-Cinerama Spherical, Aspect ratio 2.20:1 / 35 mm Anamorphic, Aspect ratio 2.35:1 Panavision

Sound Mix: 70 mm 6-Track (70 mm prints) / 4 Track Magnetic Stereo (35 mm prints)

Filming Locations: MGM British Studios, Borehamwood / Shepperton Studios, Shepperton, Surrey / Monument Valley, Utah // Production Dates: 28 January 1965 - 10 March 1968; Shooting Dates 29 December 1965 - 7 July 1966

Release dates: 3 April 1968 (USA) / 11 September 1968 (BRD) / 22 February 2001 (re-release Berlin Film Festival) / 30 March 2001 (UK, re-release)

Awards: Academy Awards 1969 Oscar Best Effects, Special Visual Effects Stanley Kubrick; Nominated Oscar Best Art Direction-Set Decoration Ernest Archer, Harry Lange, Anthony Masters; Best Director Stanley Kubrick; Best Writing, Story and Screenplay - Written Directly for the Screen Arthur C. Clarke, Stanley Kubrick // British Academy Awards 1969 Best Art Direction Ernest Archer, Harry Lange, Anthony Masters; Best Cinematography Geoffrey Unsworth; Best Sound Track Winston Ryder; UN Award - Stanley Kubrick // David di Donatello Awards 1969 David Migliore Produzione Straniera Stanley Kubrick // Hugo Awards 1969 Best Dramatic Presentation // National Film Preservation Board 1991 National Film Registry // New York Film Critics Circle 1968 Best Direction; Best Film, Best Screenwriting

Alternate Versions: The film originally premiered at 160 minutes. After the premiere director Kubrick removed about 20 minutes worth of scenes and made a few changes: A few scenes in the "Dawn of man" opening section and on the moon where the monolith is discovered where shortened; Many scenes detailing routine life of the astronauts aboard the "Discovery" spaceship were removed; The titles "Jupiter Mission, 18 months later" and "Jupiter Beyond the Infinite" were added between sections; According to rumors the premiered version also included scenes set in present-day New York and featured an explainatory voiceover for the "beyond the infinite"-trip section.

2001 was shot with a 5-perf 65mm (2.20:1) negative using spherical lenses, which is the format originally called Todd-AO and then Super Panavision (when Panavision built cameras & lenses for the format).

"2001" has got "Cinerama" in the credits, but technically to SHOOT in "Cinerama" means using three 35mm 6-perf cameras built into a single-unit with their three 27mm lenses holding a 146 degree field of view, with an aspect ratio of approx. 2.60:1.

When Pacific Theaters bought the Cinerama Corp. they stopped the use of the difficult 3-camera format and used either spherical 65mm (Todd-AO / Super Panavision) or anamorphic 65mm (MGM Camera 65 / Ultra Panavision) and put the "Cinerama" label on it.

"2001" was projected using 70mm prints onto curved Cinerama screens, but the negative format itself for "2001" is 65mm 5-perf spherical. It's not a mix of two different shooting formats called "Cinerama" and "Super Panavision." Probably that duel label was meant to describe the 70mm release of the film for curved Cinerama screens and ordinary flat screens.

|